The Islamic Discourse of Visual Propaganda in the Soviet East Between the Two World Wars (1918-1940)

Vladimir Bobrovnikov

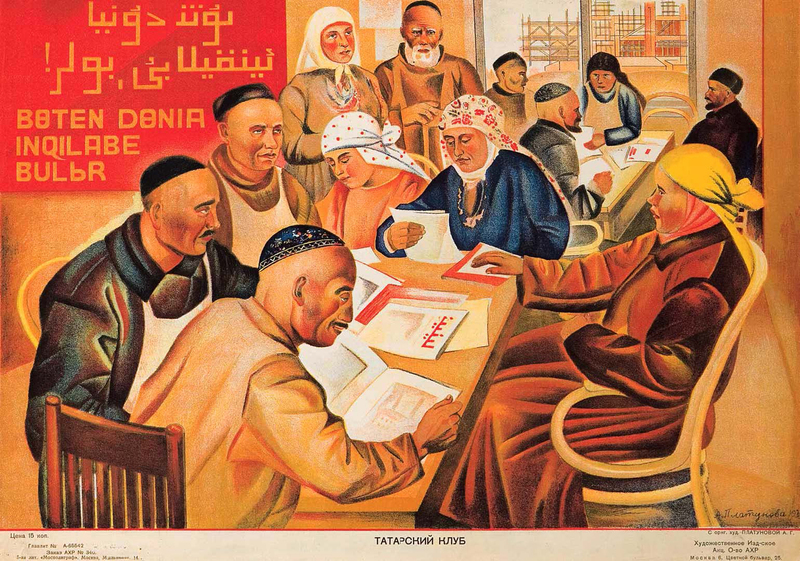

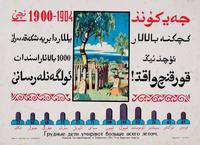

Visual propaganda played an enormous role in the history of the 20th century. In contrast to the 19th century, it was aimed not only at the educated classes of the mother countries but also at the masses in the colonies of the great powers, including vast territories in the east and south of the former Russian Empire. The posters created for Muslims (and with the participation of Muslims) between the two world wars in the Soviet East – in the Volga Region, in Crimea, in the Urals, in Siberia, in the Caucasus and in Central Asia – represent an enormous and as yet little-studied layer in the history of Soviet propaganda. To some extent their popularization was promoted by an exhibition that was held with my participation at the Museum of Contemporary Russian History (the former Museum of the Revolution) in Moscow in 2013 and the catalog that was published for it, which was the basis for this article.[i] Even so, the majority of Eastern posters remain unknown to the public at large. Only certain Eastern versions of works by such classic Soviet political cartoonists as Dmitry Stakhievich Moor (Orlov) (1883-1946); Viktor Nikolaevich Deni (1893-1946); Nikolai Nikolaevich Kogout (1891-1959); Aleksandr Mikhailov Rodchenko (1891-1956); and Kukryniksy[ii] received wide renown during the Soviet period.

Historical Context of Political Propaganda

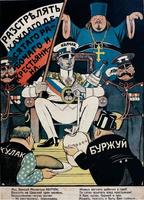

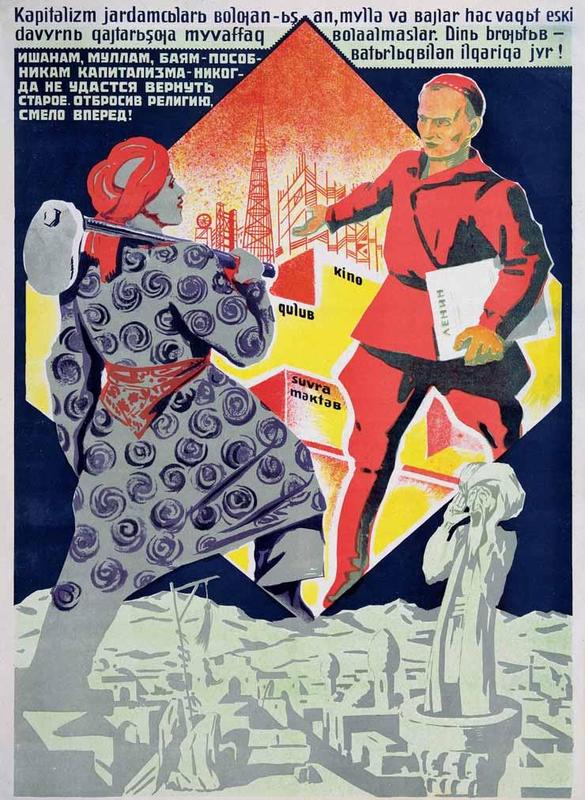

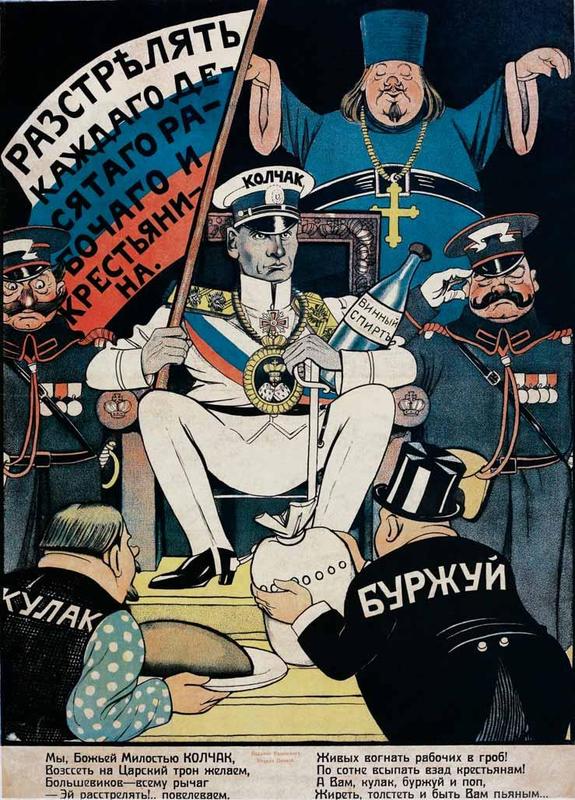

During this fantastical, painful, ruthless period, various parties and factions rapidly succeeded one another in power. The content, language and style of posters would change accordingly. Posters were not a mere reflection of historical realities. It was the truth, but certainly not the whole truth, and at times not the truth at all. During the Civil War the Reds’ posters accused the Whites, primarily Admiral A. V. Kolchak and General A. I. Denikin, of the mass annihilation of working people (9), even though the Red terror resulted in no fewer casualties among the civilian population. White Guard propaganda, in exactly the same manner, kept quiet about the Whites’ punitive expeditions.

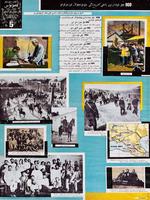

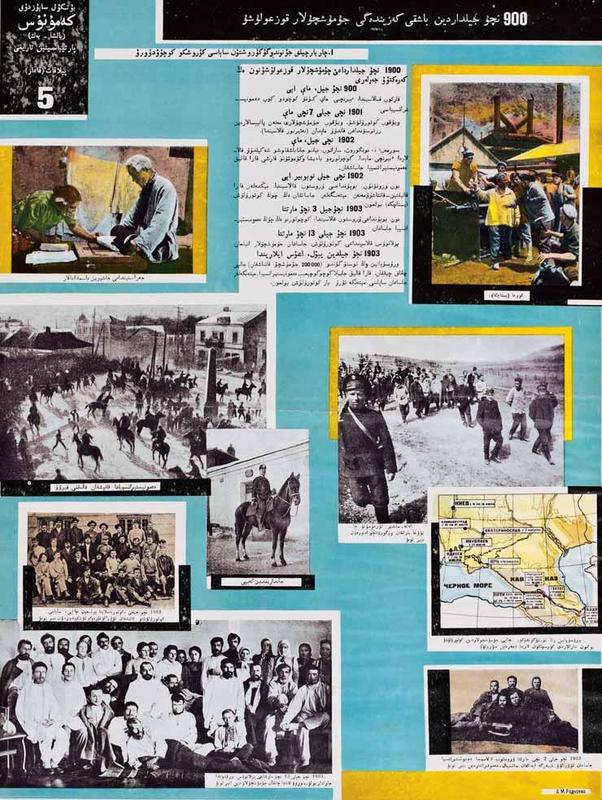

By way of wishful thinking, many figures and photographs were put on the posters of the 1920s and 1930s. During the first Five Year Plan (1928-1932) a whole style of photo montage (22–25, 143, 156, 201, 241) emerged.

It is worth noting that during those years photo montage also became popular in the West, including in Nazi Germany (compare: 1-2dop).

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Rodchenko, a Constructivist artist who was a friend of Vladimir Mayakovsky and one of the leaders of LEF [the Leftist Front of the Arts], was one of the first to use this genre in posters on the history of the workers’ movement and Soviet construction projects (23-24).

This feature of visual propaganda should be kept in mind when studying the seemingly objective information that posters contain. On the one hand, the figures with which posters are sprinkled precisely repeat official Soviet statistics and the major quotations of party and government leaders. The proofreaders of state publishing houses kept close track of their fidelity to the originals. At the same time, however, these quantitative indicators contain many contradictions. For example, if one compares the statistical data on mosques shut down in the 1930s, one is struck not only by the magnitude of the figures, which are many times greater than the data in prerevolutionary reports on mosques, but also by the difference between data from various areas.

The situation becomes clearer if one recalls that during the period 1932-1937 the so-called “godless Five Year Plan,” which was aimed at forgetting God’s name in the USSR by 1 May 1937, was under way (3dop). Socialist competition developed over who would be the fastest to shut down more mosques and madrassas. Everything falls into place if we recall that the figures on the posters served above all the purposes of agitation.

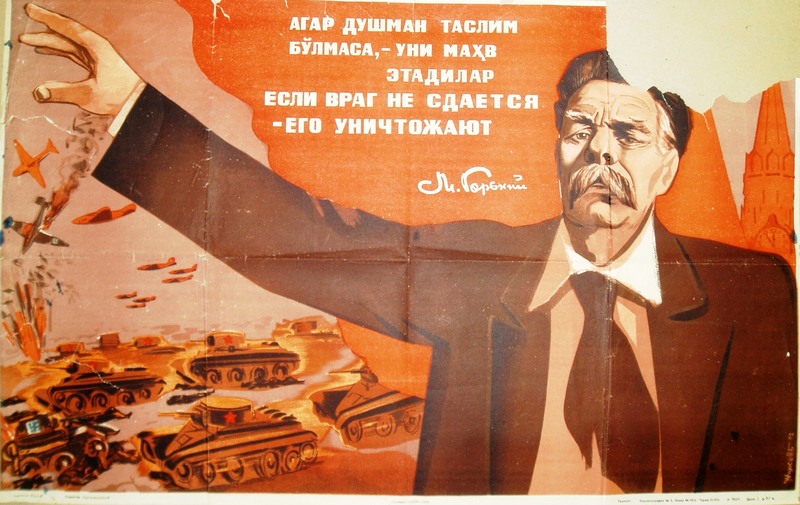

It is not difficult to expose the lies of official propaganda. Similar to Rostopchin’s leaflets during the Patriotic War of 1812, Soviet posters hid the shame of defeats and economic devastation under cheery pictures of imagined victories. A poster from the period of the Finnish Campaign, from which the Red Army emerged extremely worn out, depicted a dashing Red Army soldier bayoneting Finns. On posters from the time of the Soviet troops’ retreat in 1941-1942, a powerful Red soldier chops up small black Kraut fascists while on horseback. A patriotic poster by Kukryniksy, “We’re giving them a sound thrashing and stabbing them furiously – we are the grandchildren of Suvorov, the children of Chapaev,” was created in 1941, when “we” were getting a sound thrashing and were being furiously stabbed by the Germans. During the days when the front got as far as Moscow itself, a poster was printed in Tashkent that depicted an offensive by Soviet tanks (4dop). They are blessed by Maksim Gorky, stretching out to the east his right arm and the famous quotation, “If the enemy does not surrender, he will be destroyed” (from a 1930 editorial in the newspaper Pravda).

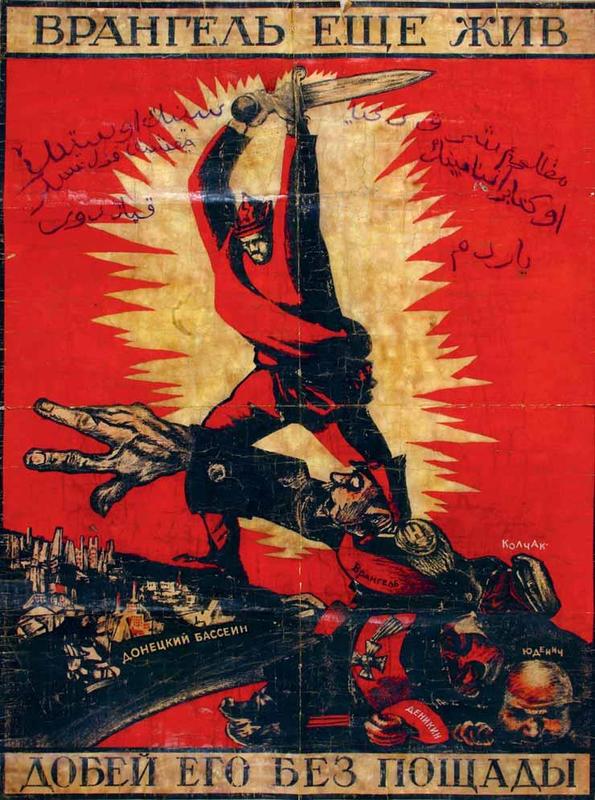

Essentially this was in the tradition of the propaganda of the Civil War period. Recall, for example, Moor’s poster, “Wrangel is still alive! Finish him off without mercy” (6), which appeared in the summer of 1920, when units of Wrangel’s army were approaching the Donets Basin, planning a drive toward Moscow.

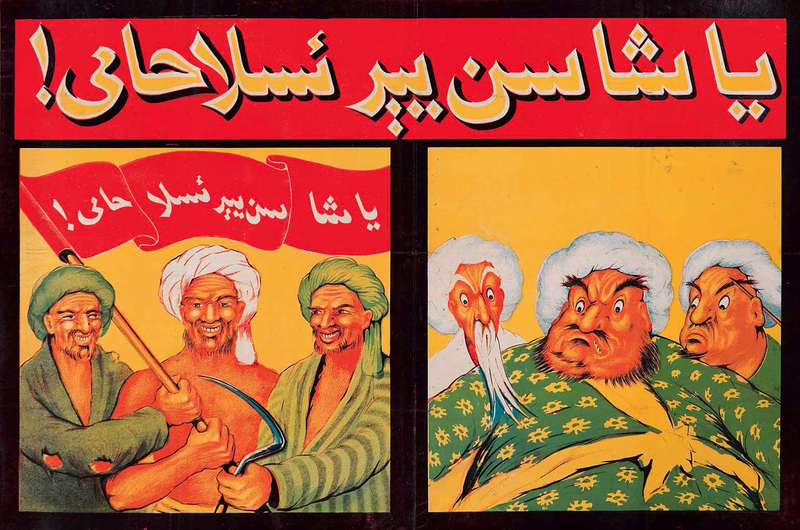

The Theater of Orientalism

Poster artists consciously simplify reality by utilizing a contrasting range of colors. Harsh colors – without transitions and shadow – create an impression of a break between the “old regime” and the capitalist encirclement (they are represented in the margins or in the lower part of a poster by the blackest colors) and what given to the working people by collectivization, industrialization and the cultural revolution (71, 90, 161, 165, 180).

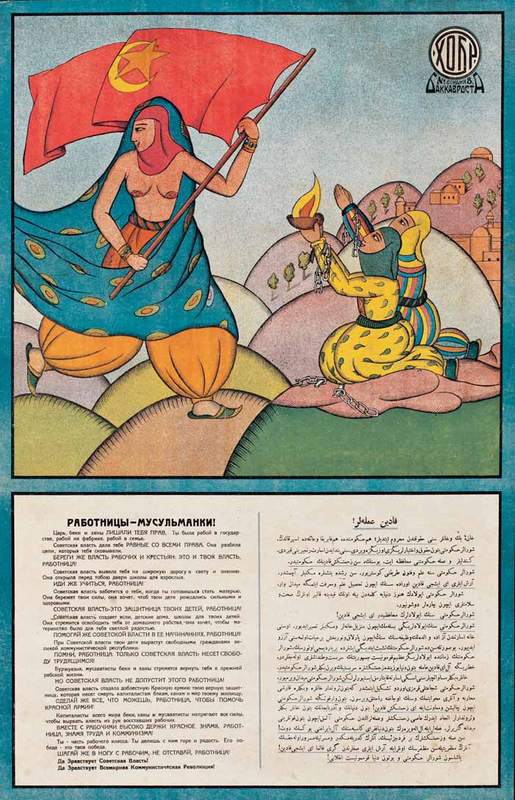

The state symbols of interwar posters were defined by the fervor of nihilistic negation of the pre-Soviet state. The poster artists liked to put on them detritus of the imperial seal, crown, the scepter and the orb, which were destroyed back during the February Revolution (9). Juxtaposed with the heroics of the Soviet present are the grotesque figures of the foreign East, in which crowds of emaciated working people collapse under the yoke of predatory exploiters. Some of the posters could serve as wonderful illustrations for E. Said’s book “Orientalism.” This pertains, above all, to the image of the downtrodden women of the East who, with a wave of the artists’ magic wand, have passed from medieval slavery into a futuristic Soviet paradise. For example, on a 1921 Baku poster a half-naked mountain woman who has cast off her parandja ebulliently marches under a red banner through the mountains to Muslim women languishing as slaves of “tsars, beys and khans,” who extend shackled hands to her (218). Such fantasies were terribly far removed from the realities of the Caucasus and Turkestan. They were too theatrical – it was no accident that the first poster artists included many set designers.

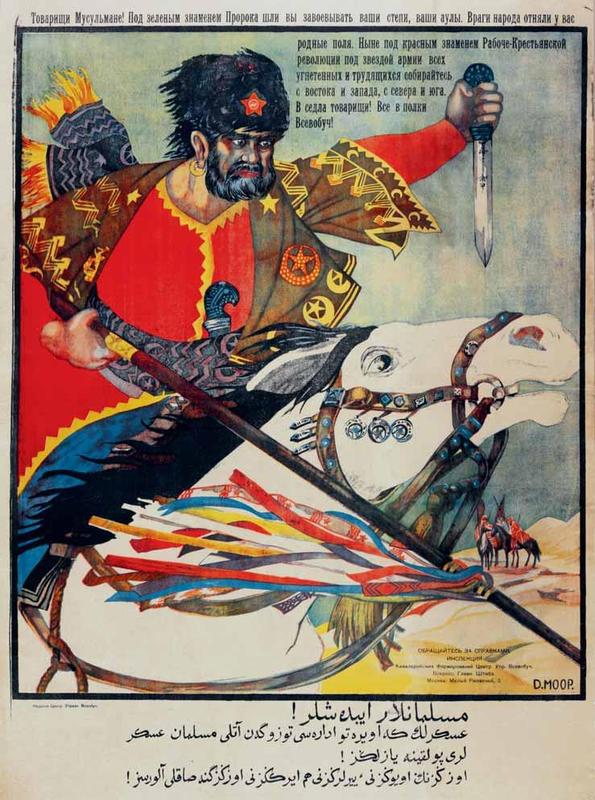

During this period Soviet propaganda still had a fuzzy concept of its potential allies in the Russian Muslim East. The posters addressed to Muslims contained too much Eastern exotica and fanciful theatrical poses. The horseman in a papakha [tall fur hat] with a red star looks like he leaped off a playbill on a 1919 poster by Dmitry Moor that calls on Muslims to enroll in the cavalry courses of VSEOBUCH [Universal Military Training]. This organization was in charge, until the universal military obligation was introduced in 1923, of the training of volunteers to serve in the Red Army. He is riding a white horse with a lance tilted forward and an unsheathed dagger. In the distance a group of horsemen is visible in robes against the background of a tent among the sand dunes in the desert (5). The poster reflects the strong influence of images of Muslim exotica in the vein of 19th-century Orientalism. Everything in it is fake and and far removed from reality. Red Army cavalrymen did not wear papakhas. They would have simply fallen off when the horsemen galloped. The harness and abundance of melee weapons that the rider has look quite odd. He is holding the dagger like a theatrical hero, running the risk of stabbing himself in the event of some impact. The Orientalist impression from the drawing is intensified even more by the long appeal inscribed in the Russian and Tatar languages, done in the Cyrillic and Arabic scripts: “Comrade Muslims, under the green banner of the Prophet you marched to conquer your steppe and villages. The enemies of the people took away your indigenous fields. Now, under the red banner of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Revolution, under the star of the army of all of the oppressed and working people, come together from the east and west, from the north and south. Saddle up, comrades! Everyone join the VSEOBUCH regiments.”

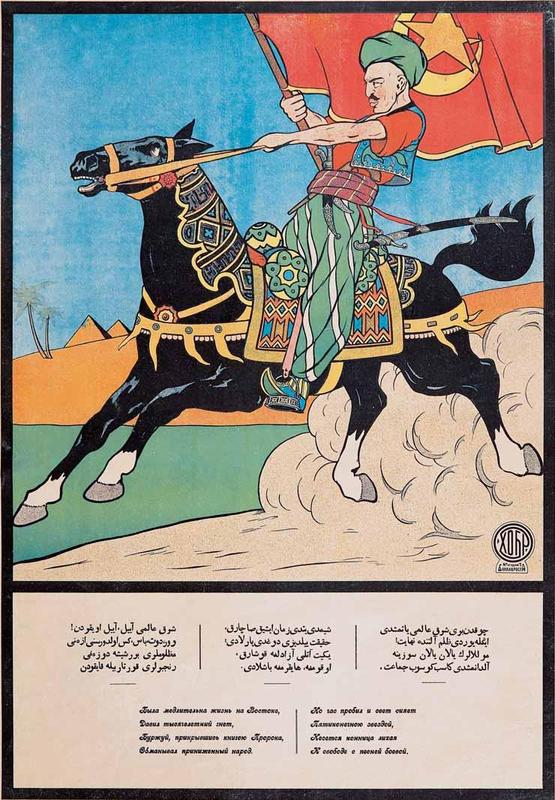

In the verses of an unknown author published by BakKavROSTA [Baku Office of the Caucasus Krai Branch of the Russian Telegraph Agency] on one poster in the Art Nouveau style, one can see polemics with M. Yu. Lermontov’s famous lines about the deathlike sleep of the East, written during the era of the Russian conquest of the Caucasus in the 19th century. In his poem “The Dispute,” Lermontov wrote:

“I fear not the East,” Replied Kazbek,

“The human race there

Has been asleep eight centuries already,…

As far as the eye can see,

All is asleep, cherishing quiet…

An unknown Soviet opponent disagrees with Lermontov, noting that the Red Army brought the East not only liberation from a colonial yoke but also opened up for it the dynamics of a modern society:

Languid was life in the East

Oppressive was the thousand-year yoke.

The bourgeoisie, hiding behind the Book of the Prophet,

Was misleading the demeaned people.

But the hour has struck and the light is shining

Like a five-pointed star,

The valiant cavalry is rushing

Toward freedom with a fighting song.

Above these uneven verses is a drawing of a liberator-horseman resembling a Turk, under a red banner with a star and a crescent. He stops the galloping horse in midair. Behind him is the yellow sand of the desert and the pyramids of Egypt, which suggest that, in the poster creators’ opinion, the Reds’ capture of Baku in 1920 was merely a temporary stop en route to the liberation of British and French colonial Africa (3). It is interesting to note that, despite all of its anticolonial fervor, this poster continues the Orientalist visual sequence. This is indicated by the very figure of the friendly Turk, his exotic Eastern attire, the landscape and the cult of ruins on the horizon.

Quotations

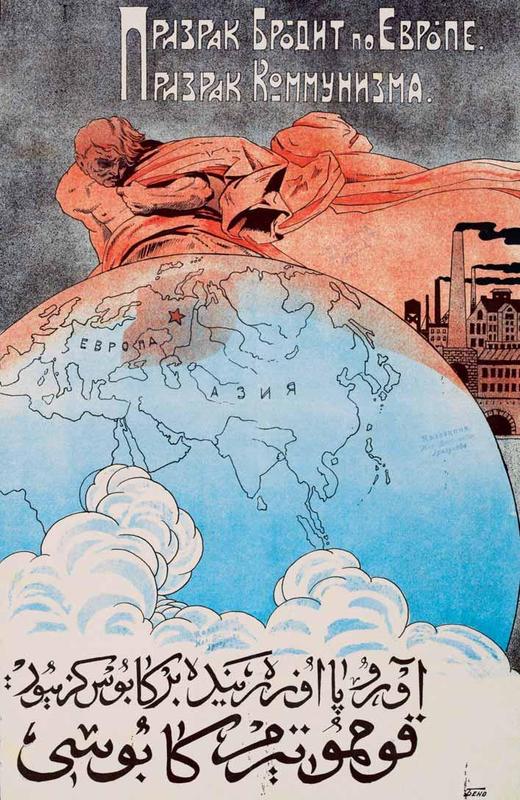

Soviet posters always included many quotations. An aphorism from the famous “Communist Manifesto” of Marx and Engels is illustrated by a 1920 poster by Beno Teligater, issued by Bakinsky Rabochy, containing a drawing of the planet Earth with capitalist Europe and colonial Asia facing the viewer (7). A giant proletarian casts a shadow on the mainland from the north, which occupies the territory of the Russian Republic with a red star in the location of its capital, Moscow. The heading, “A Specter is Haunting Europe – the Specter of Communism,” is written in Russian and Azerbaidzhani (in Arabic script).

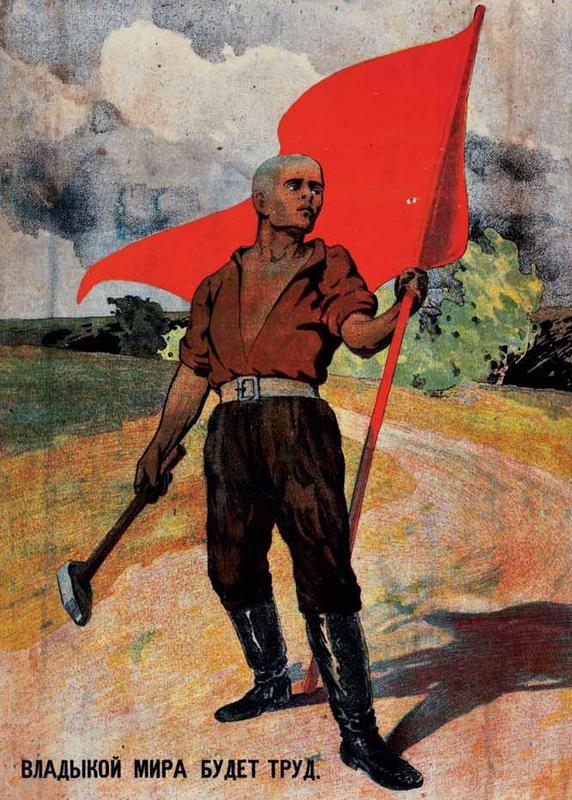

The headings of the posters of the period often contain excerpts from poems and songs of the revolutionary movement that were popular at the time. Many of them have long since been forgotten and cannot be identified, while for others the source can still be determined. For example, a poster issued in 1920 by the State Publishing House in Kazan (39), depicting a worker under a red banner, is called by the last line of a hymn of Polish insurgents of the 1890s that was translated into Russian:

Down with the tyrants! Off with the shackles!

We don’t want the yoke of slave chains!

We will point Earth to a new path --

Labor shall rule the world!

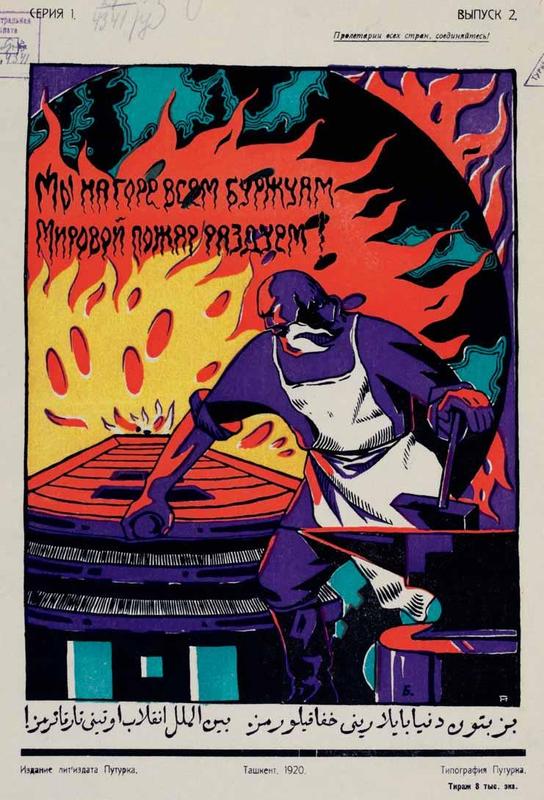

A poster with a worker by a red-hot forge, issued in the same year in Tashkent by the Literary Publishing House of the Political Directorate of the Turkestan Front (PUTURKOM), is based on an excerpt from a Red Army song, which was based in turn on A. Blok’s famous poem “Twelve” in Russian and translated into Uzbek (in Arabic script; 14):

We shall whip up a worldwide fire

To the great sorrow of the whole bourgeoisie!..

The spontaneity of the revolutionary upsurge of the masses that the artists of early Soviet posters liked to depict became a subject of sharp criticism by the VKP(b) in the late 1920s. Demands were made that the poster creators show the leadership of the proletarian party as a revolution and subsequent socialist construction. Posters began to include an increasing number of extensive quotations from speeches by the leaders of the party and the state, resolutions of party congresses and conferences and portraits of the leaders and ideologues of the Bolshevik party, above all Stalin, Lenin, Marx and Engels. By the 1930s quotations from the leaders of the Revolution had become so ingrained in the compilers of the texts for Soviet posters that at times they were put on them without a caption or quotation marks (133-137).

Languages and Translations

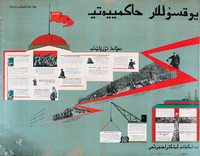

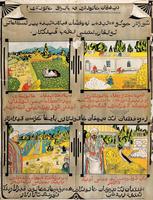

Posters for the Soviet East up to the mid-1920s, as a rule, were bi- or multilingual. They were composed in Russian and translated into one (or several) national languages of the former Eastern minorities of the Russian Empire. In the Volga Region, Crimea, the Urals, the Caucasus, Turkestan, Western Siberia and the Kazakh steppe, Arabic script was used, adapted for the specific characteristics of the local Turkic, Persian and Caucasian dialects (‘adjam). The Arabic written language, sacred to Muslims, continued to be used as the language of government, law and culture. During the first decade of its existence, the Soviet government was still oriented toward the prerevolutionary experience of interacting with the empire’s former subjects. The authorities of the empire, and then of Soviet Russia, would translate their appeals into literary Arabic, Farsi and Ottoman Turkish. The headings and captions of the posters were intended for the few literate elites. It was no accident that the artists inscribed them in scripts that were customary there: usually in regional versions of Naskh (2–5, 7–8, 10–14, 22–25 and others), printed in the Volga Region and Central Asia and handwritten in the Caucasus,

more seldom with elements of ornamental Kufi (53)

or Ta’liq (76, 212, 216).

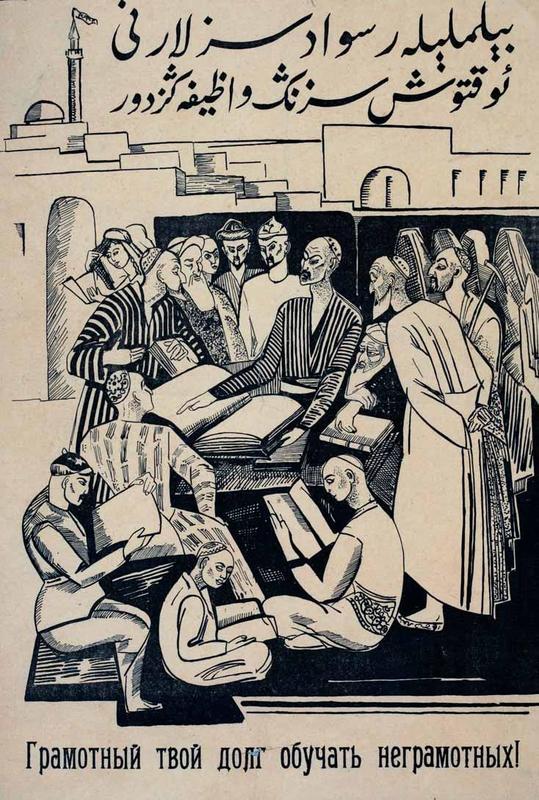

A poster would address the illiterate in the caustic language of cartoons.

The transition at the end of the 1920s from Arabic script to the Latin alphabet was caused primarily by the state’s struggle against Islam and religion in general. In addition, it stemmed from the hopes for a world revolution, which was being prepared by the Comintern and the numerous organizations associated with it, such as MOPR (the International Organization for Assistance to the Fighters of the Revolution), established in 1922. What attracted the creators of the new alphabet about the Latin script was that it was more widespread than Cyrillic. Initially the plan was to use it as a basis for the creation of alphabets for the languages that previously used the Arabic or other writing system, based on religious tradition, and then convert it to a Latin foundation and Russian. The conversion of the languages of most of the peoples of the USSR to Cyrillic was a result of the orientation toward the victory of socialism in an individual country. Under Stalin it was elevated to the rank of indisputable dogma. This occurred during the adoption of the 1937 Constitution and stemmed from the launch of the new Soviet Russification project. A common script served the process of erasing ethnic differences in order to form a new community – the Soviet people. At the beginning of the 1930s, however, posters continued to be released in Arabic script.

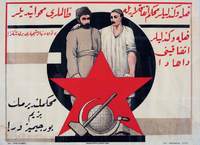

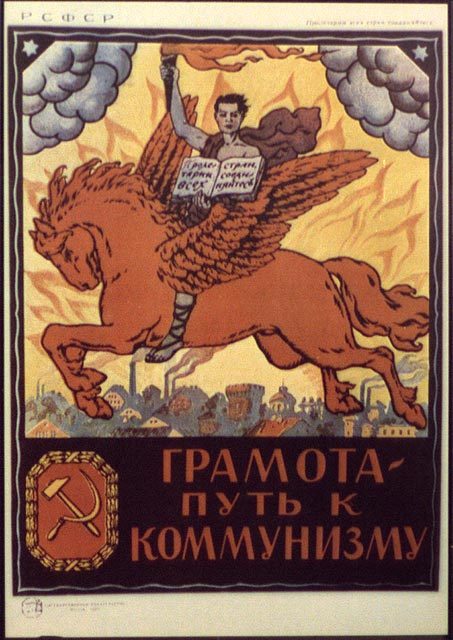

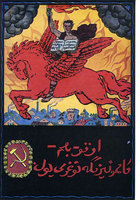

For the most part, the themes and symbols of the posters reproduced quite closely the repertoire of the Russian-language propaganda leaflets that were being issued in the RSFSR for Russians. Their style is identical. Workers are drawn as giants on them, while representatives of the old world are depicted as harmful black insects. They are trash and parasites that have engorged themselves from the blood of the working people, which they sucked out under the tsarist regime. This uniformity is largely attributable to the hierarchical, centralized character of Soviet propaganda. The topics and texts of the posters were sent out to the centers of the Union republics and autonomous republics and oblasts from Moscow. Some of them were released with minor variations in tens of thousands of copies. For example, in 1920 a poster by an unknown artist, “Reading and writing is the path to communism” (5-7dop), was issued in Russian in Moscow in a print run of 50,000 copies. It depicted a youth with a torch and an open book, flying on a fiery-red winged horse. Exactly the same poster, with a slogan written in Russian but with the title in Azerbaidzhani in Arabic script, appeared in the same year in Baku. Similar posters were printed in Arabic script for Turkestan and in Yiddish in Hebrew script for Jewish settlements in Ukraine and Belorussia.

Styles and Artistic Influences

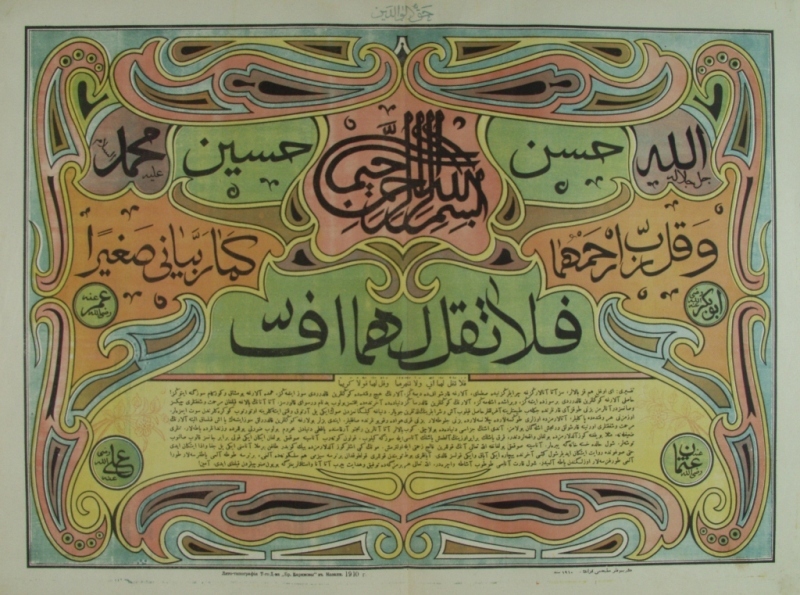

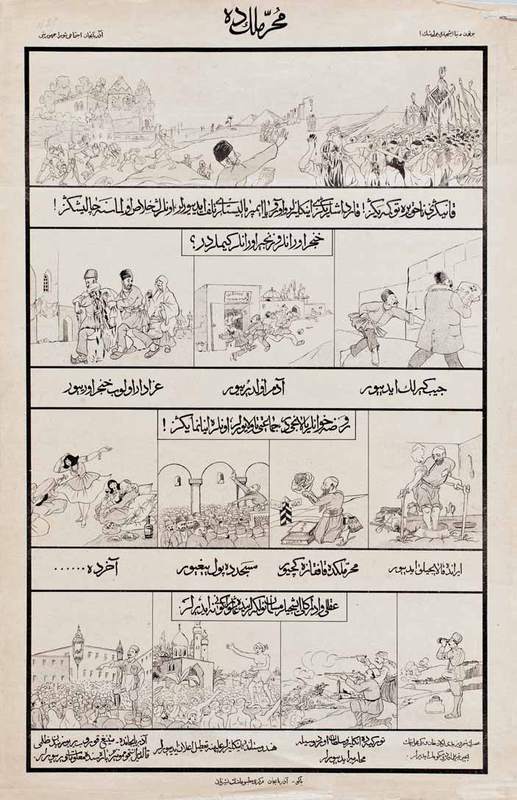

The style of images of the 1920s reflects the most diverse prerevolutionary artistic influences. A decade later, the variety came to an end. The iconography of images assumed the monotonous and mandatory forms of socialist realism, which by the time of the Patriotic War had experienced the influence of the Russian patriotic style of the end of the imperial age. But one can see among the authors of the 1920s the influences of earlier eras. And that is not surprising. After all, many poster artists had begun in journalism during the decade before the Revolution. In order to subsist during the hungry years of war communism and the beginning of NEP, a lot of artists made extra money on the side by drawing posters. Genre drawings that resembled the Western comics of the interwar era med from magazine cartoons to posters. Posters in the Muslim East during the 1920s showed the influence of the Art Nouveau style, and a little later of avant-garde art and Constructivism, as well as the traditions of folk woodblock prints and Tatar calligraphic drawings – shama’il. That is what the pious verbal portraits of the prophet Muhammad were originally called in Ottoman Turkey, Iran and Russia’s Volga Region. Shama’il flourished as a separate genre of figurative art at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century in the Middle Volga Region, above all in Kazan (which later became one of the centers of the issuance of posters for the Soviet East). The texts that formed the drawing itself in it were mostly poems. What ties them to the latter is a genuine piety toward the written word. It is worth noting that Soviet posters and cartoons, especially during the Civil War and the beginning of Soviet cultural reforms, also often contain verses, albeit in the form of a deliberately simple, and sometimes indecent ditty.

The creators of Soviet anti-Islamic posters did not so much follow as reject the style of the prerevolutionary age. Compare a 1921 poster calling on the young people of Turkestan to join the Komsomol with a shama’il on one’s duty to one’s parents, printed in Kazan in 1910 (174; 8dop). The artistic style of both, especially the vignettes of the shama’il, reflects the influence of Art Nouveau with its love for queerly winding lines. But the theme of the relationship between fathers and sons is resolved by them in different ways. The Kazan shama’il, with reference to the ayat [verses] in the Koran, demands that children, even when their parents have grown old and cannot help the young people, treat them with respect and not say “Phooey” to them. This is written in large letters in the center of the drawing. The poster for Turkestan, conversely, rejects the need to heed parents’ advice that is inconsistent with the epoch of the Soviets, calling on young people to all but not give a hoot about them. Here a girl who has decided to join the Komsomol has turned away and is not listening to her parents or the mullah, who are calling her back to the mosque.

Soviet political cartoons were especially influenced by the genre artists who worked in the traditions of the denunciatory painting of the 19th-century Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers). It is typical that the last chairman of the Association of Peredvizhniki, Pavel Aleksandrovich Radimov (1887-1967), headed the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR, and from 1928 on, AKhR). A speech by Radimov at the 47th touring exhibition “On the Depiction of Everyday Life in Art” became the association’s program. It called on Soviet artists to be guided by genre features that are “understandable to the people’s masses” in the realism of the late Peredvizhniki in the portrayal of “the everyday life today of the Red Army, of workers, peasants, leaders of the revolution and heroes of labor.”[i] These propositions made up the credo of Soviet poster artists, most of whom belonged to the AKhR. From the very first months of its existence, the Association was closely linked to the Red Army command, for which its members created hundreds of posters in the first half of the 1920s. Its branches appeared in the Northern Caucasus and in the Volga Region with Turkestan – from Nizhny Novgorod and Rostov-on-Don to Astrakhan and Tashkent. Later the AKhRR was joined by a number of organizations of avant-garde artists, such as the Jack of Diamonds, which was famous at the time (1926). In 1932 the AKhR was the basis for the establishment of the Soviet Artists’ Union.

[i] Gronskii, I. M., and V. N. Perel’man (compilers). AKhRR. Sbornik vospominanii, statei, dokumentov. Moscow, 1973, p. 19.

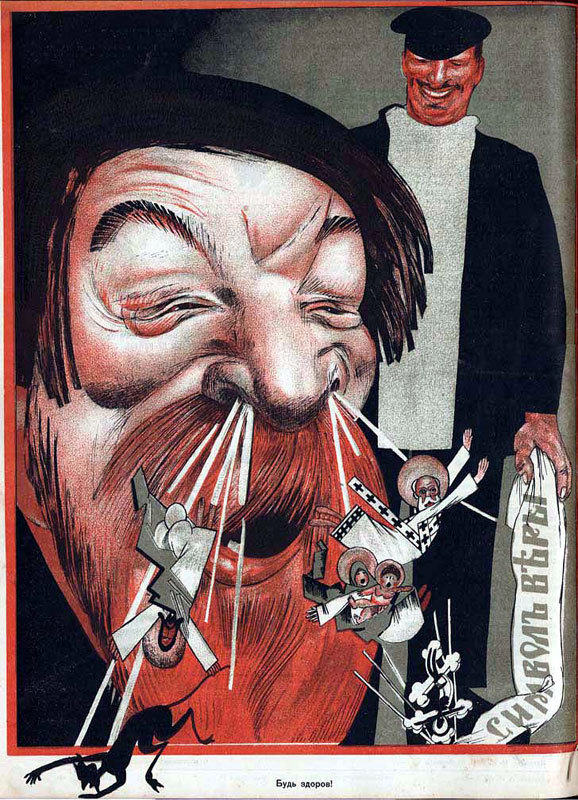

Antireligious Propaganda

Soviet poster artists inherited a harsh antireligious fervor from the Peredvizhniki. One of the poster artists’ favorite themes was initially cartoons along the lines of Karl Marx’s thought, paraphrased by Lenin, that “religion is the opium of the people.”[i] Lenin’s denunciations of “spiritual booze” were reinforced many times over by the poster artists, who expressed them in extremely harsh form. A fat Orthodox priest with a large, gold-plated cross on his potbelly personified on the posters one of the rulers of the old world who had been overthrown by the revolution but had continued to plot against it in league with the White Guards and domestic enemies of Soviet Russia (the “bourgeoisie” and the “kulak”).

[i] Marx, K. “Einleitung zur Kritik der hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie,” in Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 1844, p. 71; Lenin, V. I. “Sotsializm i religiia,” in Lenin, V. I. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. 5th ed., vol. 12. Moscow, 1968, p. 143; Lenin, V. I. “Ob otnoshenii rabochei partii k religii,” in Lenin, V. I., ibid., vol. 17, Moscow, 1968, pp. 416, 423, 425; Lenin, V. I. “Klassy i partii v otnoshenii k religii i tserkvi,” in Lenin, V. I., ibid., vol. 17, p. 438.

In the regions he was complemented by ministers of “other” religions, such as a shaman with a drum on a 1921 Yakutsk poster, “Get away from the scoundrels! Come with us!” (9dop).

Especially clever (albeit blasphemous) cartoons against religion were created by Mikhail Mikhailovich Cheremnykh (1890-1962), who was close to Moor. The main target of their attacks was Russian Orthodoxy, its dogmas and the Orthodox clergy (10dop). As for Islam, which was practiced by the masses of the indigenous population of the Caucasus, the Volga Region and Central Asia, the treatment of it by the Soviet government, and hence by poster artists, was more cautious. Only during the period when the antireligious campaign was particularly intense in the 1930s were poster artists no longer afraid of abusing the religious feelings of Muslim believers as well.

One should not demonize the Soviet period by depicting it as a time of brutal persecution of religion. The government and believers in Soviet Russia were not always on different sides of the barricades, as is customarily believed. The state’s religious policy fundamentally changed more than once, and the periods of cooperation between the Soviet government and religious organizations, on the whole, occurred more often and lasted longer than the times of antireligious persecution. The period of open war against Islam was brief. It began with the first Five Year Plan and lasted until the beginning of the Great Patriotic War. Later, during “the Thaw,” under Khrushchev, a new round of persecution began, but it was no longer at all comparable to the mass repressions of the 1930s. During the 1920s the Bolsheviks cooperated a great deal with the Muslim elites. In certain areas of Turkestan and the Northern Caucasus, Soviet rule was established with the support of the Jadids, a modernist movement that sprang up in the Russian East and the Middle East in the 19th century. In Russia its initiator was the prominent public-affairs writer Ismal-bei Gasprinsky (1851-1914), the founder of the newspaper Terdzhiman. The movement was not very influential in the outlying Eastern regions of Russia, but played a big role in early Soviet cultural construction. The Jadids were characterized by a worship of knowledge, which was adopted, partly through them, by Soviet poster artists.

The Contribution of the Jadids

Like the Bolsheviks, the Jadids believed in social progress. In contrast to the Bolsheviks, however, the Jadids maintained that the criterion of this progress was not the revolutionary reorganization of the whole world, led by the party of the proletariat, but the preservation by Muslims of their Islamic identity so long as there is technical progress and education of the people. The Jadids worked in the first Soviet secular schools and issued the first Soviet newspapers and magazines, including those with a satirical orientation. Among the leaders of this orientation in Turkestan was Abdal Rauf Rakhim-ogly, better known under the pseudonym Fitrat. After Soviet rule was established in Tashkent in 1918, he founded the Chagatai Conversations cultural society there, published the magazine Tang (“Dawn”) beginning in April 1920, propagandizing the creation for the Turkic-speaking peoples of a common writing system on the basis of the Chagatai dialect, and was people’s commissar of education of the Bukharan Republic (1920-1922).

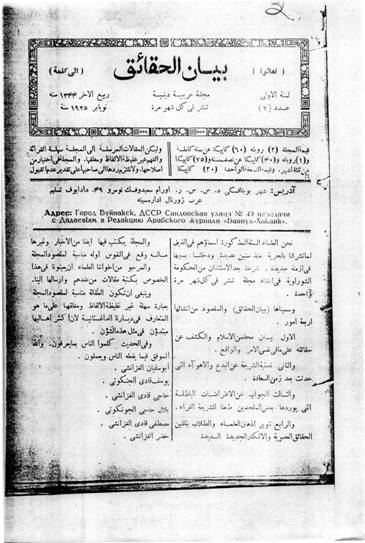

From 1925 to 1928 the Dagestani Jadid Abu Sufian Akaev (1872-1931) published the Arabic-language magazine Bayan al-Khaka’iq (“Clarification of [Sharia] Truths”) in the town of Temir-Khan-Shura, where he offered Islamic justifications of Soviet reforms (11dop). Together with his like-minded colleagues among Dagestani scholars, such as the Jadid Ali Kaiaev (1878-1943), he spent a great deal of effort on translating into Sharia language the populist Soviet laws on land nationalization, cooperatives and universal public education.

The Poster Artists

Even before the Revolution the Jadids reformed Arabic script for the languages of the peoples of the Russian East, changes that Soviet poster artists subsequently put to use. Most of the posters, though, were drawn by non-Muslims. Among them were Russians, Russified Germans, Letts, Armenians and Jews. One of the best known cartoonists working in this area was Dmitry Moor of adopted his pseudonym in honor of Karl Moor, the irreverent son and rebel and hero of Schiller’s “The Robbers.” Like another classical artist of Soviet political posters, Viktor Deni (Denisov, 1893-1946), he started as a cartoonist at the prerevolutionary satirical magazines Budilnik [The Alarm Clock] and Utro Rossii [Morning in Russia]. The famous Kukryniksy were Moor’s pupils.

The palette of visual propaganda was no less varied and complex in the Soviet Caucasus between the Civil War and World War II than in the capital of the country. The region had well-developed traditions of prerevolutionary Muslim public-affairs commentary, including political cartoons in the magazine Molla Nasreddin. Tiflis and Baku had their own publishing houses and printing plants, which during the Soviet period became major centers of state propaganda. Poster artists in the Caucasus represented a multitude of artistic schools. There were realists and there were adherents of avant-garde art, which was active in Transcaucasia and Dagestan in the first half of the 1920s: Cubists, Futurists, Constructivists. Quite a few outstanding Orientalist works were also created there during that period. When the Civil War broke out, the notable St. Petersburg Acmeist poet and artist Sergei Mitrofanovich Gorodetsky (1884-1962) was living there. He had started working in Tiflis and Baku in 1916 as a war correspondent for the Petrograd newspaper Russkoe Slovo [The Russian Word]. Until he left for Moscow in 1921, he took part in making the first Soviet posters. “Here in the Great East, a friendly clash between two arts and cultures – those of Asia and Europe – is taking place, the artist Pavel Chichkanov wrote in the first issue of the magazine Iskusstvo [Art] for 1920-1921, which was being published by Gorodetsky. “A collision of two comets. The East of fairy tales and dreams. The East of manuscripts, frescos, rugs and engravings and Europe with its Cubism, Futurism and Suprematism. Painting in painting. Take the East’s ability to “make a thing.” Take it and apply it to the entire complexity and richness of contemporary thought and feeling. And you will get a golden age of art.”

In 1919 Solomon Telingater (1903-1969), the son of the set designer and illustrator Beno (Benedikt) Rafailovich Telingater, established a branch of ROSTA Windows in Baku– a studio of BakKavROSTA. From 1921 to 1925 Telingater headed the art studio of the Baku House of Communist Indoctrination. A group of talented poster artists took shape around him. Beno Telingater Sr. also made posters. During the first Russian revolution already he became a cartoonist and worked at the Baku satirical magazines Dzhigit and Zianbur (1906-1920). For a while the notable Futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov (1885-1922) worked at BakKavROSTA; he tied his work to Soviet visual propaganda during the Civil War, which took him to the Caucasus.

Many poster artists came to Central Asia together with the Red Army. Many of them concurrently decorated sets while working as designers at the theater, and later in the movies. In September 1920 Ilia (Ruvim) Moiseevich Mazel (1890-1967) founded, under the Political Department of the First Army of the Turkestan Front in Ashkhabad, the Advanced School of Arts of the East, which specialized in posters. One graduate of that school was the well-known poster artist Mikhail Voldemarovich Reikh (1904-1966).

The first Muslim cartoonists began to work at the magazine Molla Nasreddin, which was published between the two Russian revolutions in the capital of the Caucasus Region, Tiflis (1906-1917). The censors shut down the magazine more than once for carrying sharp attacks against the empire’s policy in the Caucasus and in the Muslim world. In 1921 it resumed publication in Tabriz, Iran. Among its employees was the Dagestani artist Khalil-Bek Musayasul. During the Civil War Musayasul made a few Soviet posters, and in the early 1920s he emigrated first to Iran, from there to Germany, and after World War II to the United States. Early Soviet poster artists included the prominent Tatar artist Baki Urmanche (1897-1990) and Kazimir Malevich’s student Aleksandr Vasilievich Nikolaev (1897-1957), who in 1920 moved to Central Asia, where he adopted Islam. He signed his works as Usto Mumin, which in Turkicized Arabic means “Faithful Master.” Both became more celebrated in painting (and Urmanche in calligraphy and sculpture as well), but they drew quite a lot of posters in their time.

State Requisitioners

The state visual-propaganda industry, which gradually took shape by the 1930s, included not only ideologues and artists but also publisher-requisitioners and censors. The role of the latter was played by Soviet government bodies that often disguised themselves as public organizations that were financed, however, from the treasury (Rabkrin – the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate; Pongola – the Committee to Help the Starving; or the above-mentioned MOPR). The requisitioners and distributors of the posters were usually identified at the bottom or the top above the frame of the drawing, together with the author’s name and printing information. The first posters for the Soviet East were issued on the basis of a requisition from the Political Directorate of the Red Army, as well as by ROSTA Windows and ROSTA Satirical Windows. ROSTA’s group of cartoonists and poster artists included Dmitry Moor; the prominent avant-garde artist and founder of the Suprematist school in abstract art Kazimir Malevich (1869-1935); and the poet of Soviet rule Vladimir Mayakovsky. ROSTA’s successor was TASS, which issued thousands of posters during the Great Patriotic War. ROSTA’s satire was aimed primarily at the external enemy, the “White Guards” and “capitalists” along with “Western colonialists.”

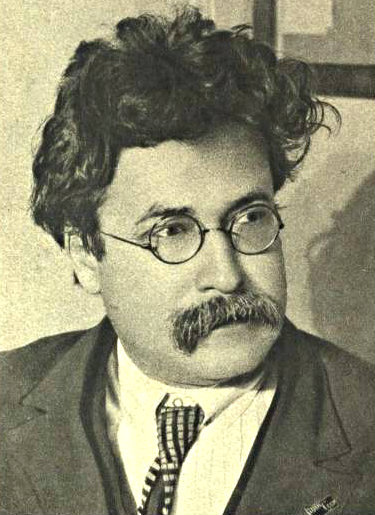

An important area of state propaganda was the struggle against religion and for the atheistic indoctrination of the masses of working people. From 1925 on, it was managed by the Union of Militant Atheists (SVB), which was replaced in 1947 by the all-Union Knowledge Society, whose successor still exists in Russia. The Union’s permanent chairman was the eminent party and Soviet leader Yemelian Yaroslavsky (1878-1943) (12dop).

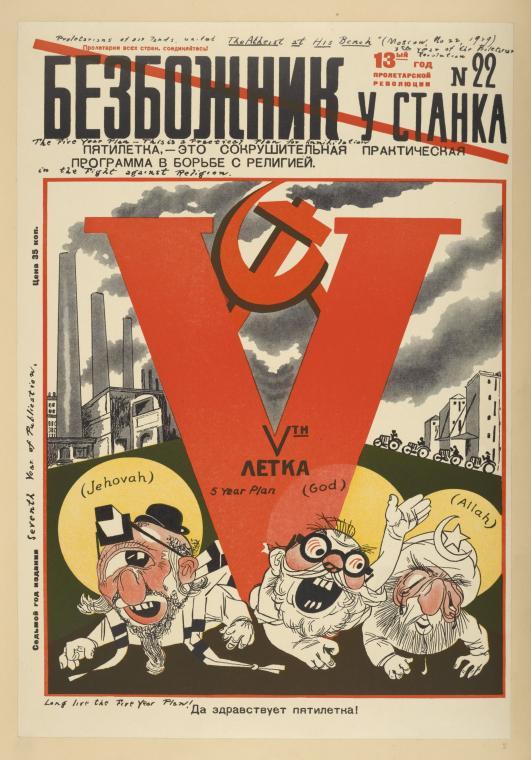

The SVB tied in the construction of a socialist society with the destruction not only of the exploiter classes but also all forms of religion. This is concisely and exhaustively expressed in the society’s slogan that was engraved on its membership badges: “The struggle against religion is the struggle for communism” (13dop). The purpose of both societies was to coordinate the efforts of the loyal creative intelligentsia and the government. The difference was that the people who worked at the Knowledge Society were mostly scholars, while at the SVB it was scientific atheists, journalists and poster artists. The Union issued a massive amount of antireligious pamphlets, newspapers and magazines.[i] The best-known ones with the largest circulation were Bezbozhnik [Atheist] (1923-1941) and Bezbozhnik u Stanka [Atheist at the Lathe] (1923-1931). The art director of both from 1923 to 1928 was Dmitry Moor.

In Central Asia, in addition to the SVB publications, there were the illustrated satirical magazines Mashrab (in Uzbek, Samarkand, 1924-1927) and Mullo Mushfiki (in Tadzhik, Samarkand, 1926-1929). They were named in honor of historical figures who were popular in Central Asia: an 18th-century dervish-satirist and a 16th-century poet, who became the hero of satirical folk stories (latifa). In Azerbaidzhan the role of Bezbozhnik u Stanka was played by the magazine Molla Nasreddin, whose publication was resumed between 1922 and 1931 by Dzhalil Mamedkulizade (1869-1932). The Uzbek-language magazine Mushtum (Fist), which started publication in 1923 in Tashkent, played an equally significant role in the development of cartoons and antireligious propaganda in Central Asia. The magazine’s head artist was Ishtvan Tullia (1923-1928). Beginning in the second half of the 1920s it had the prominent poster artists Usto Mumin (A. V. Nikolaev), Varsham Nikitich Yeremian (1897-1963), Vladimir Leonidovich Rozhdestvensky (1897-1949) and other poster artists.

[i] For more detail, see: Stykalin, S., and I. Kremenskaia. Sovetskaia satiricheskaia pechat’, 1917-1963. Moscow, 1963.

The Thematic Repertoire

The history of posters in the Soviet East began during the Civil War. Early Soviet propaganda strove to convince Muslims in the former outlying eastern regions of the empire that they and the Soviet state had common enemies: tsarism, which oppressed Muslims until 1917, and the kulaks who were continuing to exploit them in the countryside; and abroad, White émigrés and the capitalist powers of the Entente. Its objective was to make Muslims join the Red Army and, together with Russians, kill White Guards and Western interventionists.

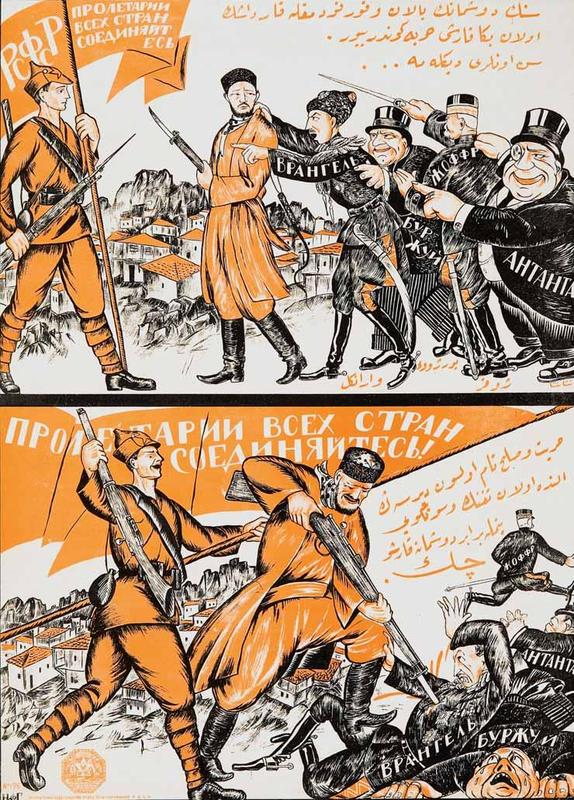

A wonderful example of such propaganda was a 1920 poster by Nikolai Kogout (Kog), which appealed to Crimean Tatars who had been drafted into Wrangel’s army to turn their bayonets against their White commanders. A caption in Arabic script in the Crimean Tatar language reads: “Your enemies are using lies and intimidation to send you to war against me, your brother. Don’t listen to them! We will secure freedom and peace! Together with me, turn the rifle and bayonet in your hands against the enemy!” The top part of the poster shows a duped Muslim with a rifle, prodded in the back by Wrangel, a bourgeois, the Entente and one of the organizers of the anti-Soviet intervention, French Marshal Joseph Joffre, moving to attack a Red Army soldier. In the lower part of the poster, the Muslim, convinced of the rightness of these words, sticks the bayonet into Wrangel’s belly (10).

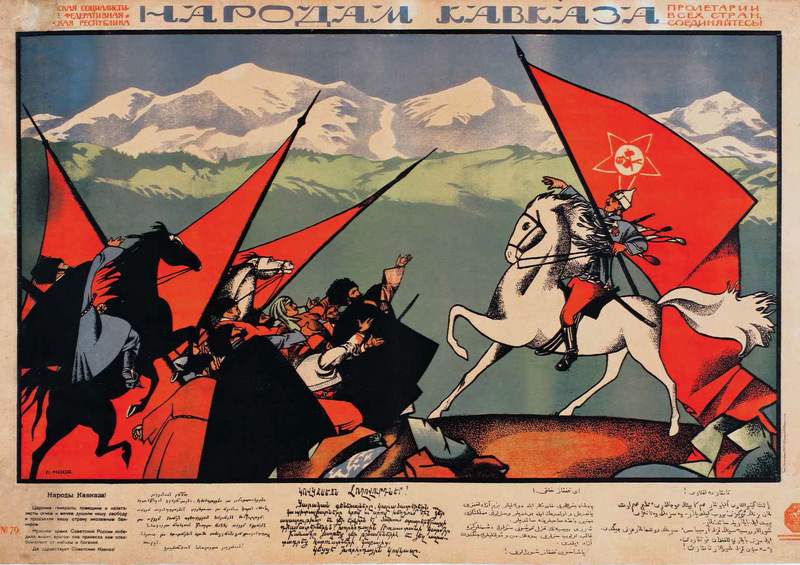

An important theme of Red propaganda during the Civil War that remained in the repertoire of Soviet posters even after it ended was the brotherhood of working people in the armed struggle for Soviet rule and in the labor exploits on the home front. Moor did a poster in its style in 1920 for the peoples of the Caucasus based on a requisition from the Political Directorate of the Red Army (PUR). Highlanders in felt cloaks, their horses prancing, extend their hands under red banners to their Red Army brother, who points out to them the oath to the communist summits above the snows of Elbrus (4). The caption under the drawing reads: “Peoples of the Caucasus! Tsarist generals, landowners and capitalists by fire and sword strangled our freedom and sold out your country to foreign bankers. The Red Army of Soviet Russia vanquished your enemies; it brought you liberation from bondage and the rich. Long live the Soviet Caucasus!” It was written in five languages. On the left is the Russian text of the appeal, and on the right is its translation into Georgian, Armenian, Azerbaidzhani and Kumyk (the last two in Arabic script). The abundance of translations was attributable to the military successes of the Red Army, whose units between January and April 1920 established Soviet rule in the Northern Caucasus; by May occupied Azerbaidzhan; and in December, Armenia. The poster was supposed to help the troops prepare a march into Georgia, which was carried out in March 1921.

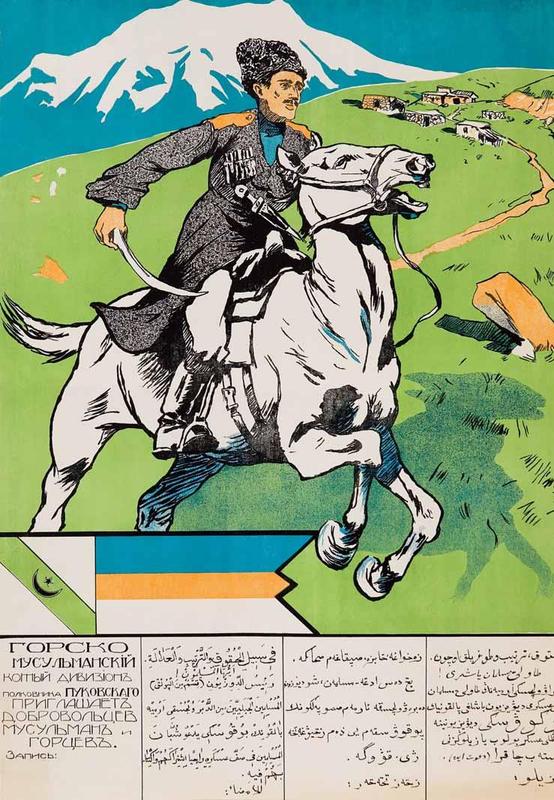

Such propaganda calling on volunteers to enlist in the army was issued by all of the combatants during the Civil War and the two world wars. A White poster that is especially memorable, issued in 1919, depicts a highlander, sword drawn, galloping through the mountains under the tricolor prerevolutionary Russian flag. The caption under the drawing called for enlistments in the Muslim highlander cavalry division of General A. I. Denikin’s Volunteer Army in the Northern Caucasus under the command of Shir-Khan (pseudonym of Andrei Fyodorovich) Berladnik-Pukovsky, colonel of the Terek Cossack Host. The division commander appealed in the Russian, Arabic, Karachai-Cherkess and Adygei languages (in ‘adjam) to mountain-dwelling blood relatives whose family members had died from Red terror. “For truth, order and justice! Muslim highlanders! Colonel Pukovsky, the commander of the Muslim Highlander Division of the Volunteer Army, invites young Muslims to enlist together in the ranks of his military detachment” (2). This propaganda had some success. According to White émigré archives, the division was assembled and fought in Denikin’s army against the Red Army in 1919-1920 near Astrakhan, in the Northwest Caucasus, and later with Wrangel in the Ukraine.[i]

[i] Berladnik-Pukovsky[, Sh.] “Soiuz Gortsev-bezhentsev Sev[ernogo] Kavkaza,” Constantinople, MS [1920s], in Columbia University. Butler Library. Bakhmeteff Archive. Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New York, box 1.

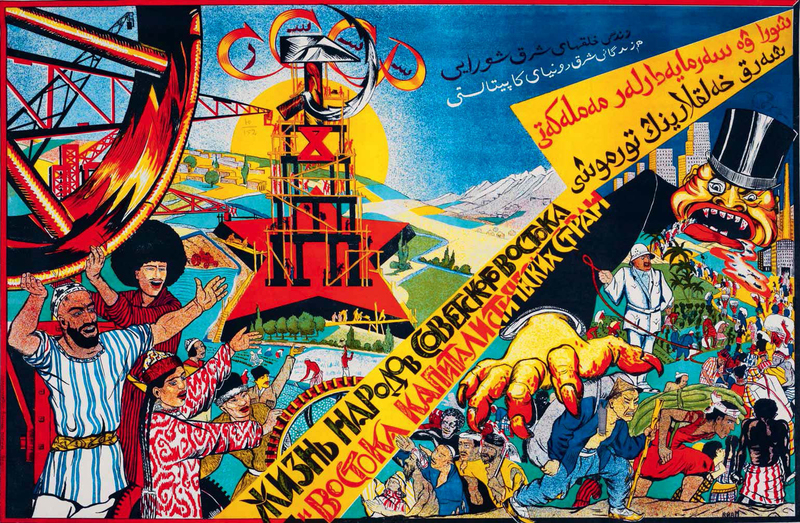

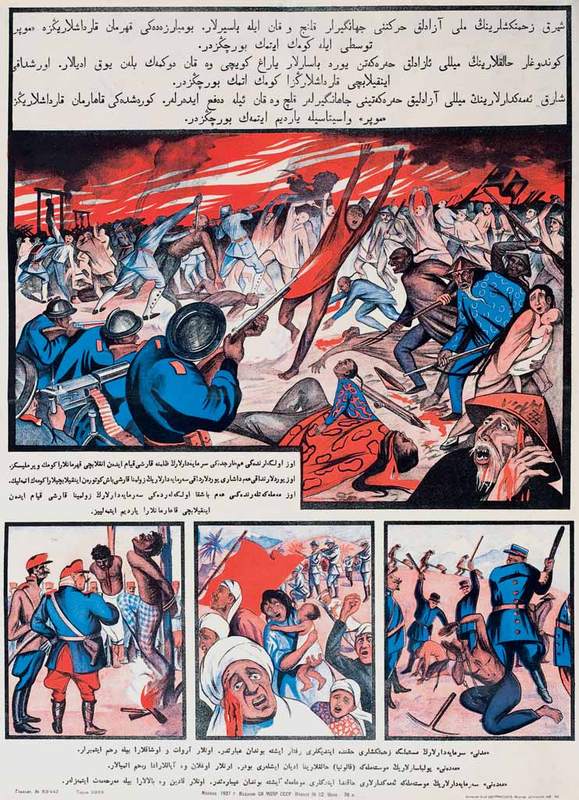

From the standpoint of the official ideology of the 1920s the triumphant march of Soviet rule in the Caucasus, Siberia and Central Asia fit well into L. B. Trotsky’s theory of permanent world revolution, which assumed that the power of the Soviets would spread to the foreign East, which at that time was made up of colonial dependencies of England and other great Western powers. This objective was served by posters that were issued during the final years of the Civil War and after it ended, which depicted the horrors of the colonial regimes and the prospects for a joint armed struggle of the working people of the East with the Red Army against the colonialists (212, 71, 213, 155).

At the same time, the creators of the posters tried to substantiate them in terms of Islamic rhetoric familiar to the Muslims of the outlying regions, which called for waging war for the faith (jihad) in order to liberate Muslims who were under the yoke of infidels. They found support in this regard among the Jadids and other members of the Muslim religious elite, which had sided with Soviet Russia in the Civil War. The theme of a Red jihad became a leitmotif of a whole host of all-Russia Muslim congresses held between 1916 and 1926 in Moscow, Ufa, Makhachkala and Baku. It was also reflected in the posters issued in their honor.

What was important for the ulema was its connection with Islamic geopolitics, which was constructed on binary oppositions close to the Bolsheviks. The world is divided in two. First, there is the dar al-islam – the region in which Muslims live according to Sharia law under the power and protection of Muslim rulers. It is opposed by the “region of war” between Muslims and the infidels of other religions. For tactical reasons true believers are permitted to conclude an armistice with their enemies, as a result of which a buffer zone forms between two hostile camps – the “region of truce” (dar al-sulh). But such agreements are temporary and may be violated when the preponderance of forces shifts to the Muslims. This traditional model of behavior became especially relevant in the Caucasus and Central Asia after they were conquered by the Russians in the 19th century. The Muslim ulema debated about what to do according to Sharia’s requirements. Should one quit the homeland and emigrate to a Muslim country, such as the Ottoman Empire, or can one live according to Sharia law and remain a Muslim under the Russians’ rule? The preponderance turned out to favor the latter argument, but when the Civil War broke out these debates resumed. The Jadids and Sufis who had sided with the Bolsheviks leaned toward the belief that after the liberation from tsarism Sharia would reign in Russia’s outlying Muslim regions. The region of war automatically shifted abroad. In this regard the views of the ideologues of the Muslim ulema and the Bolsheviks temporarily coincided.

The fantastical and, at the same time, creative nature of postrevolutionary propaganda was aptly pointed out as early as 1919 by the poet Maksimilian Voloshin, who found himself in Crimea during the Civil War. In the poem “The Bourgeois” he wrote about its ability to create faces of friends and enemies of the regime, who had come to life in the context of rapid changes:

There was no bourgeois but there was a need for him,

The revolution requires a capitalist

In order to overcome him in the name of the proletariat.

He was hastily slapped together out of shopkeepers, merchants,

Landowners, cadets and midwives.

He was mixed with officers’ blood,

Burned through and fused together in the Cheka’s torture chambers,

The Civil War breathed into his mouth…

Then he believed in his own existence

And came into being…

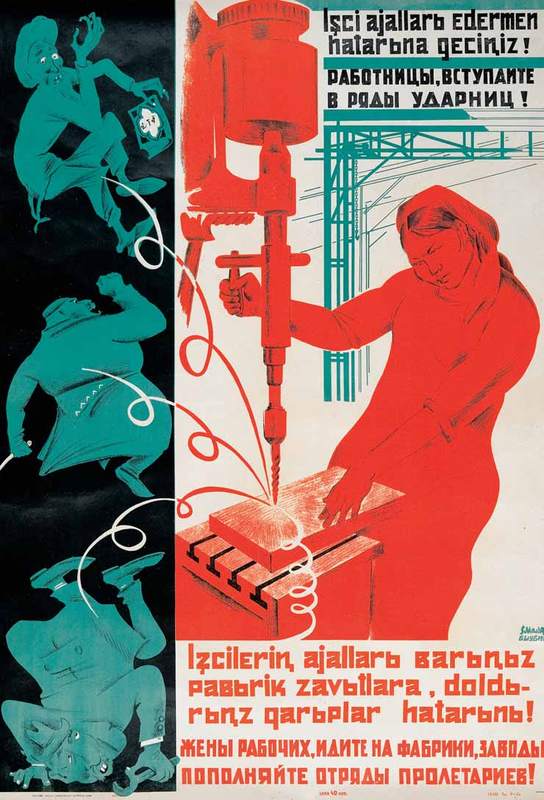

In a similar manner the figure of the“proletarian”was “slapped together” in the Soviet East, where it had previously been unknown. Since they could not find an equivalent to this scholarly Western concept, the translators of posters replaced it with the simpler word “workingman,” while replacing “proletarian women” with “workers’ wives” (97, 179, 187).

Occasionally, to translate the term they used an Arabism that was popular among Russia’s Muslims -- fuqara’, “poor people” –which until 1917 had a religious connotation of “humble,” “obedient to God.” In order to avoid needless (and unpleasant for the Soviet government) Russian Orthodox associations, the concept of “peasants” was translated on Central Asian posters with the word dehkans (Persian “landholders”) (98). The famous quotation from the Communist Manifesto and the slogan of the Soviet state, “Proletarians of all countries, unite!,” was translated into the languages of the peoples of the Soviet East as “Working people of this world (dunya), unite!” For purposes of clarity, the translators here used the Arabic term ad-dunya, which in the Islamic tradition denoted this transitory world in contrast with the eternal next world (al-akhirah).

A number of terms from the new social and political everyday routine moved to the posters of the Soviet East without translation, as copies of the Russian: “kooperativ” [cooperative], “kolkhoz” [collective farm], “kulak,” “fabrika” [factory], “raion” and “sotsializm.” In the process many Arabisms and Iranianisms entered the Soviet political vernacular, such as shura (Soviets), ittifak (union), engelab (revolution from the Persian, from the Arabic inkilab – “coup”) and islah (reform). The struggle against general, abstract concepts with prerevolutionary Islamic connotations began later, during the period of the frontal offensive against religion in the 1930s.

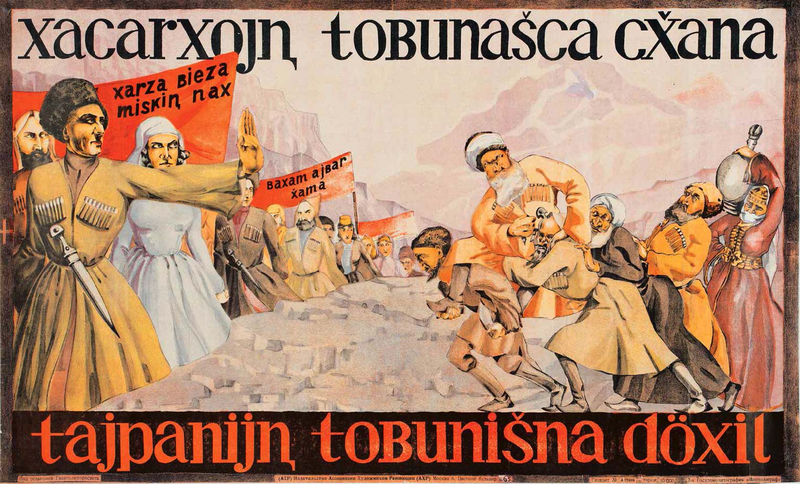

After subjugating the Caucasus, Crimea and Turkestan by force of arms, the Soviet government was unable for a long time to secure obedience from the Muslims. A years-long basmachi movement began in the deserts and mountains of Turkestan. From time to time there were uprisings in the Caucasus, especially in the Georgian mountains, Dagestan and Chechnya, the largest of which was the so-called anti-Soviet revolt, led in 1920 by the Dagestani political leader and Sharia scholar Najmuddin Gotsinsky (1895-1925). The outrage was quickly suppressed by regular army forces, but the guerrilla struggle in the mountains lasted for another few years. It was not until the fall of 1925 that Gotsinsky was taken prisoner and executed. Until then he was in hiding with his Dagestani and Chechen host-kunaks [friends] in the mountains.

Recognizing the power of local customs and clan-based everyday life as a serious, unresolved issue in the region, the secular government combated them not only with brute force but also through visual propaganda. One of the posters made in Moscow for Checheno-Ingushetia in a print run of 10,000 copies tries to persuade the mountain-dwelling working people not to elect rich sheikhs and the elders of clans (teips) to Soviets. On it, a demonstration of mountain-dwelling working people carrying Red posters with the captions “Vote for poor peasants!” does not allow in an old exploiter in a papakha with a white turban whom members of his teip are carrying on their backs (219). The meaning of the drawing is explained by a Chechen-language caption in Latin script: “Be together with the toiling masses! May the teip detachments collapse!”

Poster artists did their bit for the struggle against religious holidays. One that became a target of especially sharp criticism in the Caucasus was the self-flagellation of Shiites during Ashura, the most important date of the Shia religious calendar, involving mourning over the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, the third Shia imam Hussein, who was killed by the host of the Omayyad Caliph Yazid in the Battle of Karbala on 10 Muharram 61 AH (10 October 680 AD). The cavalry commander, Caliph Shimr, cut off Hussein’s head and brought it to Yazid. For the first ten days of the month of Muharram on the lunar Muslim calendar mystery plays are staged that re-enact Hussein’s death, flags of mourning are hung, and rouzekhans (reciters) sing folk tales about him. The 10th of Muharram is a day of a ceremonial procession, whose participants inflict bloody wounds on themselves and beat themselves with chains, by way of underscoring the grief and memorializing the blood shed by the prophet’s grandson. Those walking in the procession mourn the imam, repeating, “Shakh Hussein, wakh Hussein!” Based on this exclamation the rites of the Shia Ashura in the Russian and Soviet Caucasus began to be called “shakhsei-wakhsei.”

One can judge the character of the Soviet criticism of the Shia processions by the 1920s poster in Azerbaidzhani-language verses under the title “To Muharram” (212). The unknown author calls on believers “not to shed your blood for nothing,” forgetting that during that time “the European imperialists are killing their brothers” in the Middle East. He denounces the “hypocritical pickpockets and murderers” who wormed their way in among the self-flagellators. The chief target of his criticism are the rouzekhan crooks who “make their way during Muharram from Iran, where they are engaged in the tinning trade, to the Caucasus in order through deceit… to collect money in mosques.” He contrasts with the self-flagellators “the socially conscious workers of Muslim countries, who during the days of Ashura help the Red Army destroy the khans and beys – the Shimr and Yazid of our time – who are fighting in Turkey against the British and the Sultan’s army, who declare strikes in India against the British, who at rallies in Azerbaidzhan talk about communism, which will wipe injustice off the face of the earth…” Not content with criticizing the Shia processions of Muharram in posters, a documentary film titled “Shakhsei-Wakhsei” was shot in the republic in the mid-1920s, showing the mournful rites of the Shiites’ Ashura as a bizarre medieval superstition. In 1931 the Azerbaidzhani CEC prohibited processions of self-flagellators, but was unable to eradicate them: they continued illegally in spite of all the bans.[i]

[i] Arapov, D. Iu. (Compiler and executive editor). Islam i sovetskoe gosudarstvo (1944-1990): Collection of Documents, Moscow, 2011, issue 3, pp. 245-246.

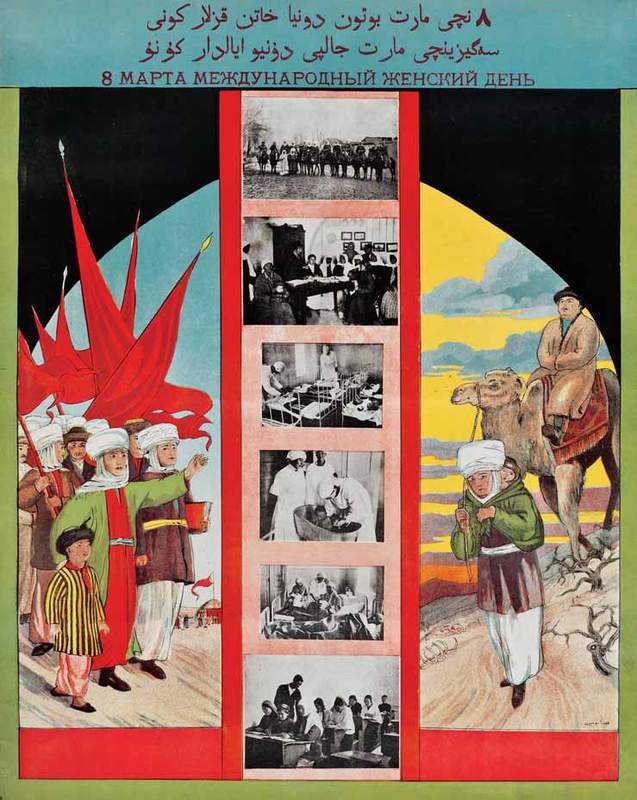

Posters contrasted the new revolutionary calendar with the Muslim holidays with the participation of foreign Muslim clergy. As early as 1918 posters began to be issued on a mass scale for the new Soviet holidays: the anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution (7 November); International Women’s Day (8 March); and International Working People’s Solidarity Day (1 May) (compare 193). Unlike Christian holidays, on which Soviet cartoons and posters commented with blasphemous aspersions, the major Muslim holidays – Uraza Bayram (the breaking of the fast at the end of Ramadan) and Kurban Bayram (sacrifices during the month of pilgrimage) – were always treated with more restraint by Soviet antireligious propaganda. Journalists even praised the Muslims’ abstinence on holidays compared with the drunken revelry that they ascribed to the celebration of Easter. The censors did not recommend that cartoonists deal with the topics of Muslim holidays. Only with the development of the Union-wide programs of collectivization and industrialization at the very end of the 1920s and in the 1930s did attacks begin on them as well. Poster artists and cartoonists joined in the ridicule. Every year on Uraza Bayram and Kurban Bayram the Komsomol began to hold parodic public processions and performances.

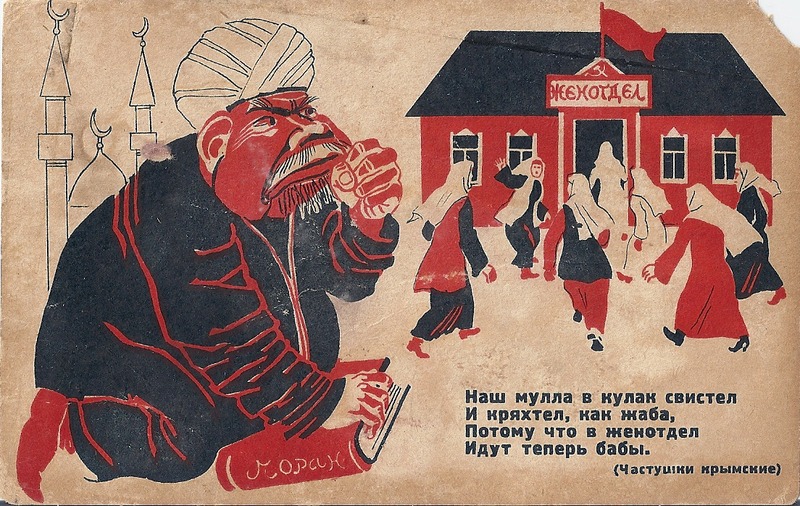

The struggle against religious holidays was closely linked in the propaganda with the women’s issue. Quite a bit of space was devoted to both of them in antireligious literature, poetry and painting. Beginning in the second half of the 1920s, so-called atheist ditties began to be circulated. In order to visualize the characterize and style of the theomachist exercises of this kind, suffice it to look at the December issue of Bezbozhnik [The Atheist] for 1925, in which the Crimean correspondent of the SVB, who hid under the pseudonym of G. Kozlov, published the following verses against the imams of mosques and Muslim holidays:

Our Mullah whistled and grunted

Into his fist like a toad

Because the gals

Are now going to the Zhenotdel [Women’s Department].

We don’t need bayrams,

Down with this thing.

What we now recognize

Is only science.

Komsomol, you, Komsomol,

We’ll march forward without fear,

We’ll drive a sharp spike into faith,

We will abolish Allah.[i]

The first couplet of these provocative and incoherent verses in that same year of 1925 was illustrated by an unknown Crimean artist. He depicted on a postcard he issued a fat, red-faced mullah in black attire. He is sitting on a big book inscribed “Quran” and is waving his fist at a flock of women in fluttering white kerchiefs who are heading for a red house with a sign reading “Zhenotdel [Women’s Department].” Barely visible in the haze behind the mullah are the colorless minarets and dome of an abandoned mosque. What is also fantastical about this scene is that in reality the mosques in most Crimean settlements were small and women did not go to them, but prayed at home, which clearly did not protect these mosques from being forcibly shut down by Komsomol members (14dop).

[i] Bezbozhnik, 1925, No. 12, p. 7.

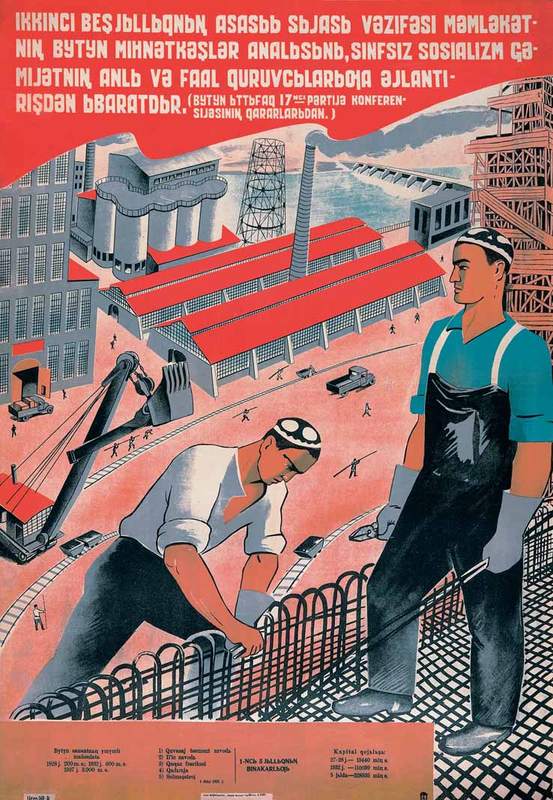

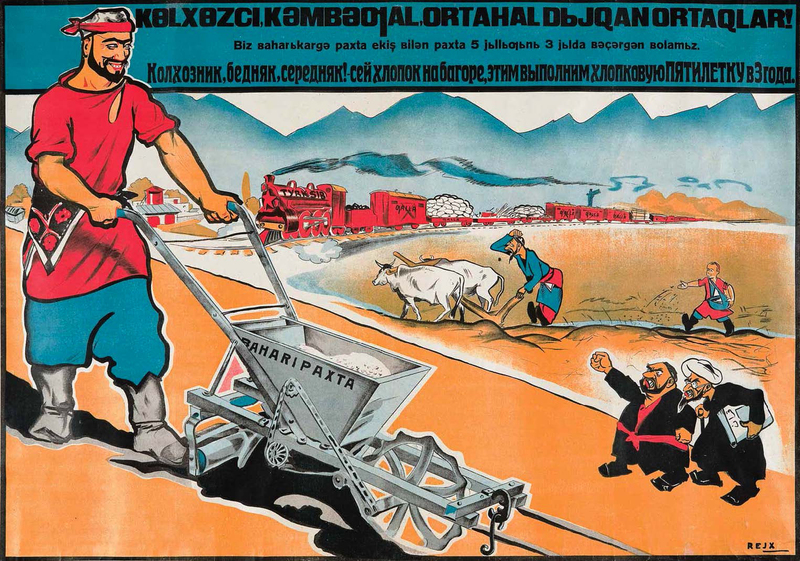

In the 1930s the international solidarity of working people, the exposure of the schemes of counterrevolutionary classes and of the fascist threat from abroad, and criticism of political conciliation and the bourgeois life of NEP merchants became important themes of Soviet propaganda. With the beginning of the first Five Year Plan in 1928, industrial construction and the urbanization of the former outlying rural areas, the land and water reform and the development of commercial cotton-growing became one of the central areas of poster painting (24, 93, 97, 108–112).

Poster artists were sent on lengthy working trips to the region’s major construction projects, the largest of which on the eve of the Great Patriotic War were the Large Fergana Canal (1938) and the Chirchik Integrated Chemical Plant near Tashkent (1940), which produced its own satirical magazine with an abundance of cartoons – Chirchikstroevsky Krokodil [Chirchik Construction Project Crocodile]. The posters of the second half of the 1930s became militarized, and they made intensive use of military symbols. A new type of Soviet “hero” took shape – the shockworker and the soldier. With the launch of socialist reforms, the theme of brotherhood among working people was overshadowed by others: the emancipation of Muslim women, the creation of general-education and labor-oriented secular schools and collective-farm construction.

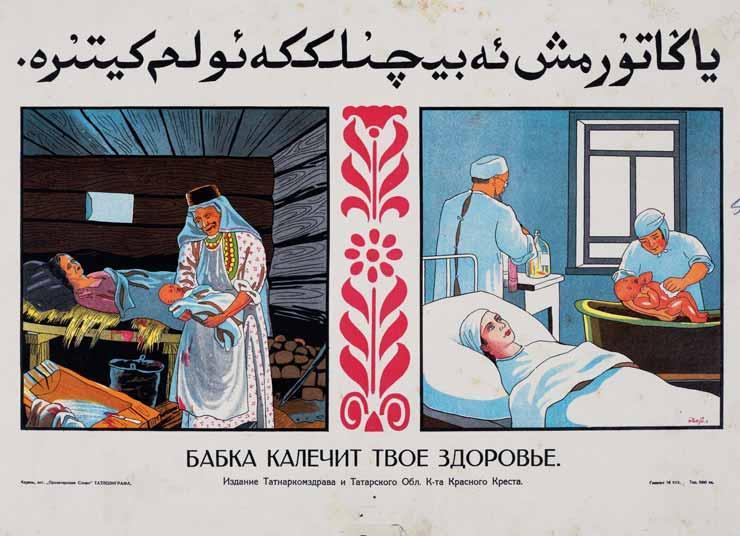

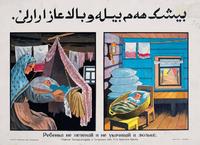

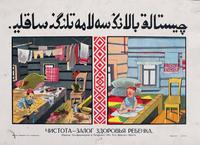

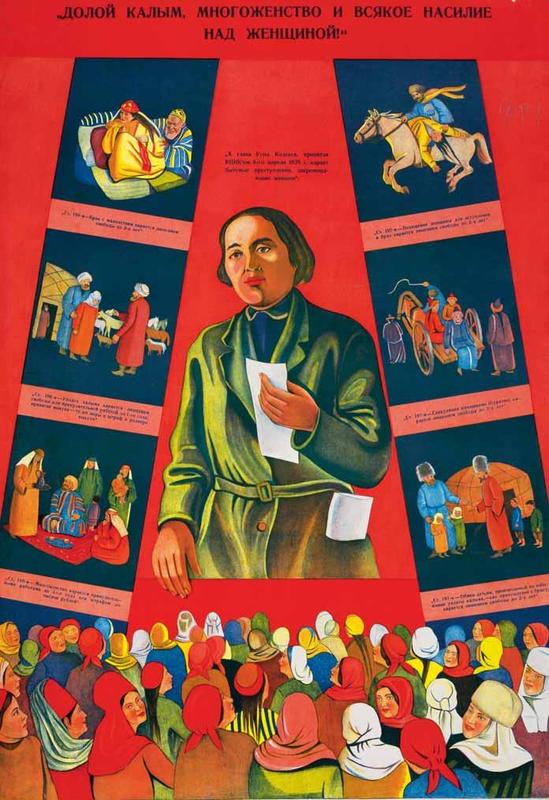

The liberation of the women of the East from domestic slavery by the exploiter-husband and the patriarchal family was one of the most popular themes of the work of poster artists. They took it up again and again.

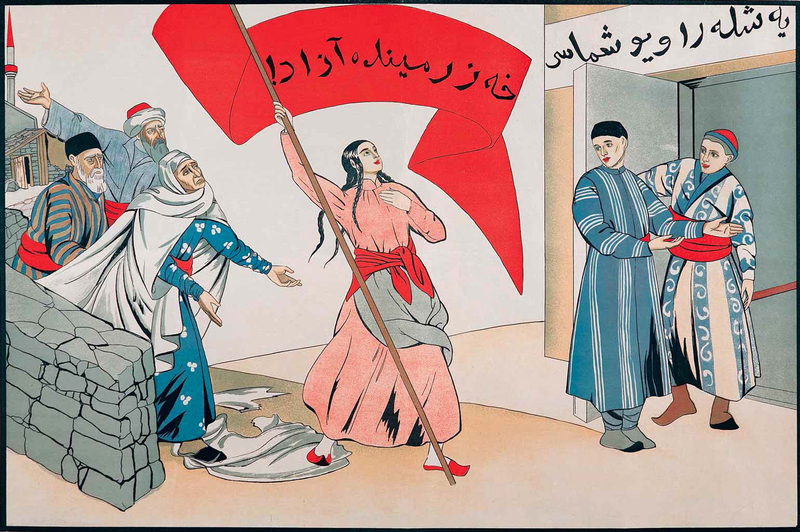

For example, on a 1921 Moscow poster that called on Turkestan’s young people to join the Komsomol, a bareheaded young Muslim girl who has trampled on her parandja, under a red banner, pushes away her parents and a mullah who are pulling her toward the old patriarchic life as she heads for the room of a Komsomol cell under the sign “Young People’s Union,” where two young Komsomol members are inviting her to come. The main idea of this work is expressed in an Arabic-script inscription on the red banner: “Now I am free, too!” (174)

Bringing female workers into public production, even in projects, was considered to be a means of such liberation. For example, on a 1931 poster by Semyon Adolfovich Malt (1900-1968) and Boris Shubin we see a female Muslim worker from Turkmenia in a red kerchief by a lathe, from which the remnants of the old world, in the form of shavings, are flying out in the guise of scary ghosts: an engineer-wrecker with a wrench, a kulak with a dagger and a mullah with the Quran (187). In Turkmenistan at the time, however, there was neither a proletariat nor a heavy industry.

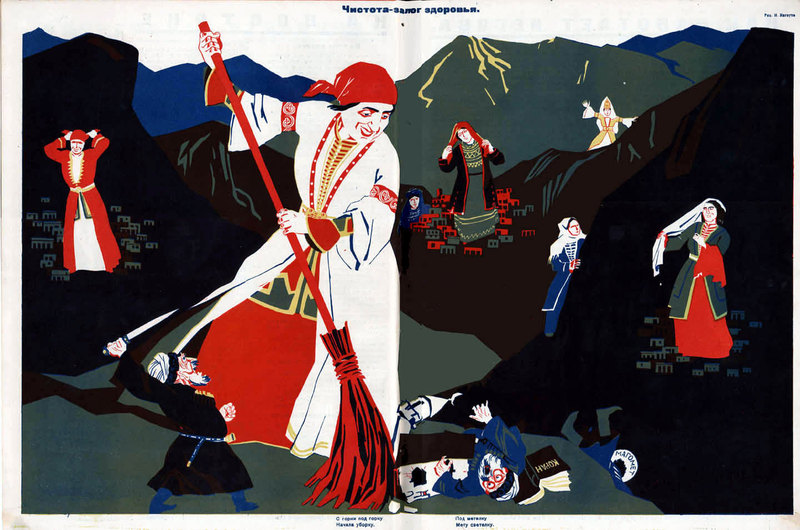

For the Caucasus, this theme was tied in with the liberation of mountain women from outdated patriarchal customs (adats). A cartoon by Nikolai Kogout in one of the issues of Bezbozhnik u Stanka [Atheist at the Lathe] for 1923 depicts a giant mountain woman in a traditional dress. Armed with an enormous broom, she sweeps all sorts of little scum from the mountain in her native village. A mosque with a minaret that the broom has smashed to pieces, a mullah with a Quran and the namesake of the Prophet Muhammad in a white turban, on which his name, Magomed, is written, go tumbling over the precipice. An old man who is an exploiter waves his dagger in impotent rage at the emancipated woman, and he is clearly also about to go over the precipice. On the slopes of the nearby mountains, she is welcomed by sister-workers from other national autonomies of the Northern Caucasus, all the way to Kabarda or Adygeia in the west, which can be recognized by the traditional high, gold-colored headgear. The cartoon is titled “Cleanliness is a guarantee of health” (15dop). Under it are the ditties:

From mountain to mountain

I’ve begun the clean-up

I sweep out the attic

To the last particle.

The concepts of this antireligious quatrain are taken from the usage of the Russian prerevolutionary countryside (attic and so forth), but were inserted in the conventional European images of the Muslim East, in which women collapse under the power of the men who shamelessly exploit them. In addition, as on the 1921 poster, the indicator of the liberated woman for Kogout is an exposed face, and less often, an uncovered head. To comprehend the meaning of these symbolic details of traditional attire, one should recall that it was precisely at that time in Dagestan that the campaign of “Down with the chukhta! Give the mountain woman a coat!” A chukhta was the name there for a woman’s traditional, high headdress that covered the hair but left the face exposed. It survived in the everyday life of mountain women until the 1930s and 1940s, and then receded into the realm of ethnographic legends. On Kogout’s drawing not a single mountain woman wears a chukhta, and the main heroine with a broom covers her head with a red kerchief, whose cut resembles the attire of the urban female workers of the time. The posters were intended to instill in the working people of the outlying eastern regions modern standards of hygiene and a health Soviet lifestyle. This topic was presented quite well not only in the Northern Caucasus but also in the posters of the Volga Region (59, 62–68).

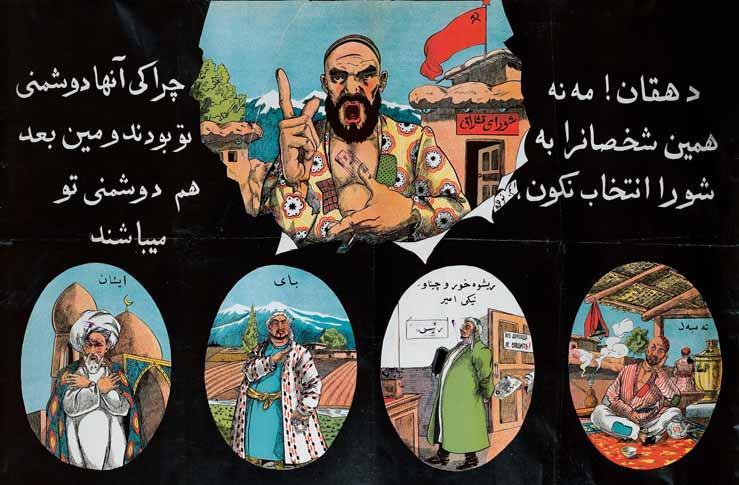

A separate large theme of Soviet propaganda was the struggle against religious prejudices. As in Central Russia, with the transition to full-scale collectivization it developed along the general lines of depicting the socialist restructuring of the Muslim countryside. From that time on, the brunt of the propaganda was aimed not at the external enemies driven out of Russia during the Civil War but at domestic enemies who were interfering with building a new life and doing all they could to harm the Soviet state and society. Posters created visual images of “enemies of the people”: kulaks who exploited poor dehkans, parasitic mullahs and the con-men ishans [spiritual leaders] who declared themselves “saints.” A portrait gallery of these negative types was presented on a Tadzhik poster at the end of the 1920s in Arabic script under the title “Peasant. Do not elect these people to the Soviet, because they were and [forever] will remain your enemies” (92).

The artist warns the dehkan not to elect to the village Soviet “loafers, the emir’s officials and bribe-takers (referring here to former officials of the Bukhara Emirate. – V.B.), bais or ishans.” The transition to full-scale collectivization served as a signal for their destruction “as a class.” Religion as a “pernicious survival” also had to be destroyed.

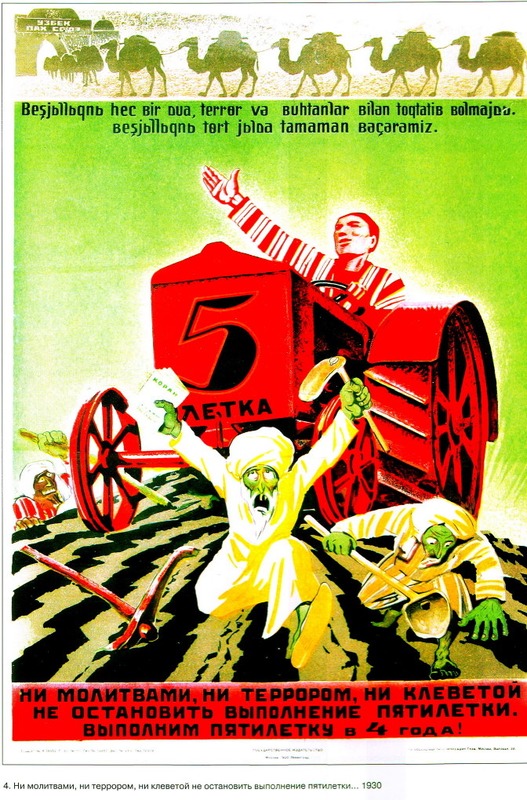

It was precisely at this time that a series of posters appeared that depicted the tractor of social progress crushing “men of the cloth” like little, harmful insects.

One such poster was created in 1930 in Uzbekistan: on it a large, red “Five-Year Plan” tractor is being driven by a boy working in a tiubeteika [embroidered skullcap] and a striped smock; kulaks are sticking spokes in the wheels but cannot stop the vehicle, which is about to catch and crush a mullah with a Quran and a wrecker with a Turkestan hoe who are running from it. The poster bears a long title in Russian and Uzbek: “Not prayers, not terror, not slander will stop the fulfillment of the Five Year Plan. We will fulfill the Five Year Plan in four years!” (16dop).

The following year the All-Union Research Institute on Cotton-Growing and the Cotton Industry put out a very similar poster in Tashkent, titled “Every piece of fallow land plowed up for cotton is a blow struck at the bais, wreckers and opportunists.” The artist Chernysh drew the plow of an “International” tractor cutting, by pressing into the land, the little figures of a former bai, an engineer-wrecker, a kulak and a mullah with a Quran in his hands (101). It was issued in several versions at once for the majority of the region’s republics in Uzbek, Kazakh and Kirgiz.

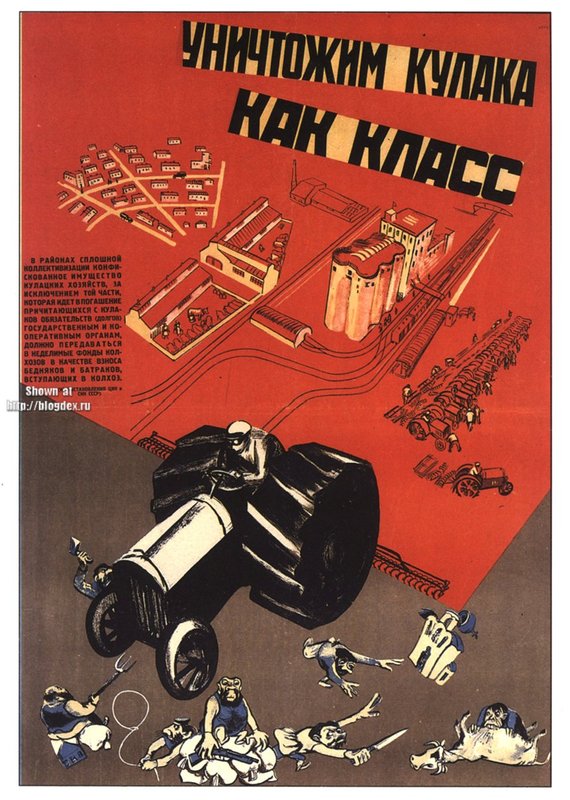

The source of these images was the Kukryniksy poster “We will destroy the kulaks as a class” (1930), which shows a large, heavy tractor smoothing out the socialized land of collective farms, and in the process wiping away kulaks, priests and churches that have been mowed down. Large-scale socialist production and the chimneys of plants are growing in the red field of the plowed-up land (17dop).

These posters appeared at the beginning of the so-called atheist Five Year Plan of 1932-1937. This was an extremely important pivotal period, when, with the physical annihilation of the Jadids who had previously cooperated with the Bolsheviks, Soviet propaganda was departing once and for all from Islamic rhetoric, the actual language of Islam, and imposing images and reality completely alien to Islam on believing and nonbelieving Soviet citizens alike. For that period’s fighters against religion, the differences between Russian Orthodoxy and Islam and the special features of various forms of Islam did not matter anymore. All of them were enemies that had to be exposed and destroyed as quickly as possible. For the functionaries on the atheist front the difference among them was, as I. V. Stalin colorfully put it, like that between “a blue devil and a yellow one.” They did not recognize either one and were trying to kill them.

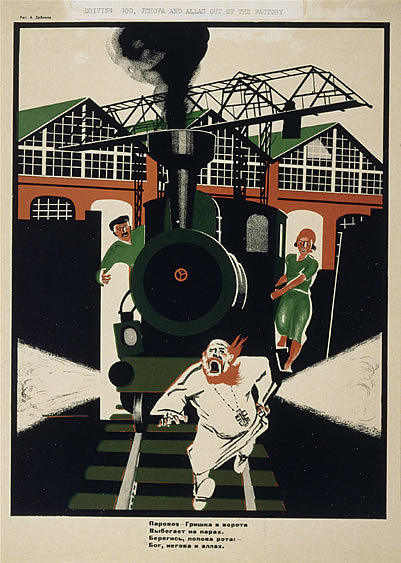

During this period quite a few cartoons appeared in which there was no particular difference between “priests” and “mullahs with sheikhs.” In one such picture from Bezbozhnik u Stanka, the well-known artist Deineka depicted a locomotive going full steam ahead, with a priest symbolizing Jehovah running in front of it (18dop). The idea of the cartoon is that God and the priest will inevitably perish under the wheels of the locomotive of history. The locomotive was thus added to the tractor as a theomachist antireligious symbol. The path itself of Soviet Russia to communism was depicted on posters as a competition between the red Soviet locomotive and the green bourgeois-fascist one.

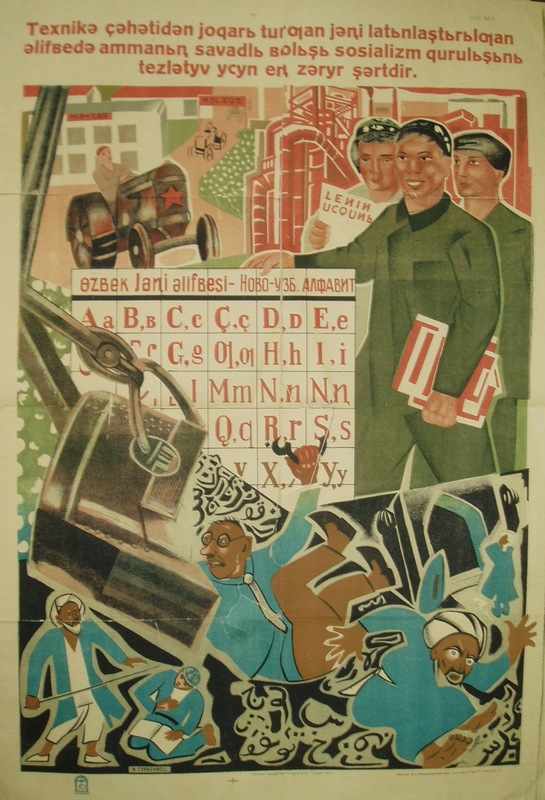

The Soviet state struck the final blow at Islam in Central Asia when total collectivization was in full swing. With two or three moves, Muslims lost their language and alphabet, which had been consecrated by a centuries-long religious tradition. To be fair, we should note that the Arabic writing system had changed quite a bit during the first decade after the establishment of Soviet rule as a result of the joint activities of modernist Jadids, Russian linguistic scholars and Soviet politicians. It underwent an orthographic reform by the Jadids, which was even more drastic than the reform carried out with the Russian language after 1917. At the end of the 1920s, unified national alphabets based on Latin script were invented for the peoples who had been accustomed to writing and reading in Arabic script. The drastic and rapid transitions from the Arabic alphabet to the Latin one, and in 1930s to Cyrillic, created entire generations in the region and the country of semiliterate people. The knowledge they had received in the early Soviet epoch found no application in public and everyday life (with the possible exception of posters, for which the writing systems that had gone out of general use continued to be used), and, in fact, could be a cause for their political persecution based on religion.

The significance of the change of alphabets for Soviet political propaganda may be judged by one of Gerasimov’s posters, “The New Uzbek Alphabet” (beginning of the 1930s), which dealt with the cultural revolution in the region (19dop). On it we see the already familiar tractor of progress driving into the sky, with the buildings of a new general-education school, collective farms and factory chimneys visible behind it. A group of stocky workers in green overalls resolutely is displaying a new Latin Uzbek alphabet in the center of the poster. One of them is holding a newspaper with Lenin’s name written already in Latin script. At the bottom, the enormous bucket of an excavator is picking up all kinds of trash, which here includes madrassas, mosques, mullahs Jadid reformers and teachers of the old Muslim school – and above all Arabic letters, sick in some way, wriggling like venomous snakes and falling together with the kulaks and mullahs. А Jadid intellectual in a necktie who has not been finished off grasps for one such letter, ayn, but he too ends up in the excavator bucket. Here, too, a scene from the life of an old school is sketched: a teacher is beating a student with a ruler.

The well-known book by Shoshana Keller on the Soviet persecution of Islam between the two world wars in Central Asia bears the symbolic title “To Moscow, Not Mecca.”[i] This sharp turn can also be seen graphically in the posters of the 1930s that were issued for the Muslims of Central Asia, in which the symbols of Red Moscow loom intrusively in the background. The Prophet Muhammad, as a model for emulation by believers on earth, and Allah in the heavens are supplanted by a single earthly supreme leader, the wise helmsman of the peoples of the Soviet Union, Stalin.

[i] Keller, S. To Moscow, Not Mecca: The Soviet Campaign Against Islam in Central Asia, 1917-1941. Westport, 2001.

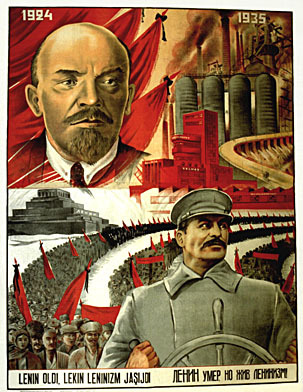

These images can already be seen on the posters in Latin script, such as Baranovsky’s work “Lenin died, but Leninism is alive, 1924-1935,” issued in Tashkent in a print run of 41,000 copies (20dop, compare 236). Columns of demonstrators with red banners are floating past the mausoleum against a background of chimneys of red plants. Conspicuous in the front ranks are the striped smocks, turbans and papakhas of people from the Caucasus and Central Asia, stylized according to the images of Uzbeks, Tadzhiks and other members of the family of Soviet peoples developed by official propaganda with the participation of scholars. They are being led by Stalin, standing at the helm in a green overcoat without epaulets and in a simple military service cap. There is simply no room in this picture for Islam. Religion has given way to the nationality-based element. Official Soviet propaganda was trying to use the posters to convey this idea to the viewer.

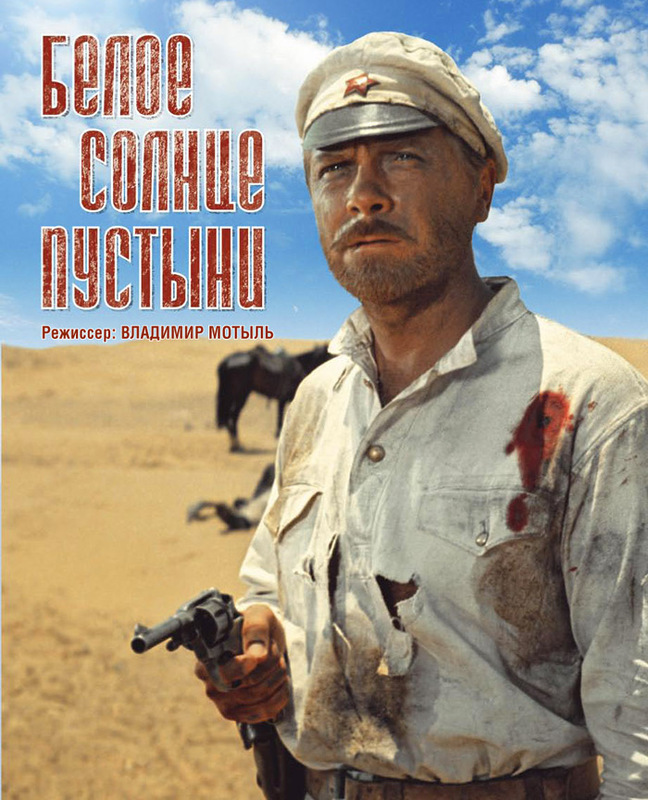

Another trend that began to receive special development in Soviet Central Asia in the mid-1920s was advertising posters for documentary and feature films. This trend also existed in Central Russia. As early as 1924, Lev Trotsky published an article headed “Vodka, the Church and the Cinema” in Pravda, recognizing in the art of film-making a powerful tool with which to fight for a healthy Soviet lifestyle. The importance of opposing religious survivals through the cinema is pointed out by a poster issued in Moscow in 1930 for the Muslims of Central Asia in Russian and Uzbek (in Cyrillic and Latin script) in a print run of 10,000 copies. It portrays a dehkan with a Turkestan hoe on his shoulder, boldly marching behind a Red worker into a colorful world of schools, film clubs and radio towers. The old religious life with the spires of mosques, a muezzin calling for prayer from them and women in parandjas on the flat roofs of houses is dispersed by pale gray smoke in the night behind him. An antireligious appeal has been made the title of the poster: “To ishans, mullahs and bais – the accomplices of capitalism: You will never be able to bring back the old. Cast off religion, and march boldly forward!”

Film showings in Tashkent began as early as 1897. In 1924, the region’s first association appeared: Bukhkino – Bukharan Cinema. Together with Proletkino, it released two feature films in 1925. One was titled “The Muslim Woman”; the other, “Minaret of Death.” The latter film depicts the prerevolutionary past and how the khans and mullahs exploited the working people and degraded women. The film has a good ending – against a revolution against the feudal lords, love triumphs, and a khan is thrown off a minaret, from where people who had tried to rebel against his authority had previously been thrown. The same year Uzbekgoskino and the film factory Shark Yulduzi appeared in Tashkent (reorganized in 1958 into the Uzbekfilm movie studio). In 1931 the director Ganiev made the film “Upsurge,” about the industrialization of Uzbekistan.

The first films shown in Soviet Central Asia included both local movies and films of studios from other regions. At the end of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s a number of films appeared on the topics of the emancipation of women and land and water reform, which had been brought up in posters. The roles of Muslim women in these films were played, as a rule, by Moscow and Leningrad actresses who had come in: the emancipation of the women of the East had not yet gone that far.

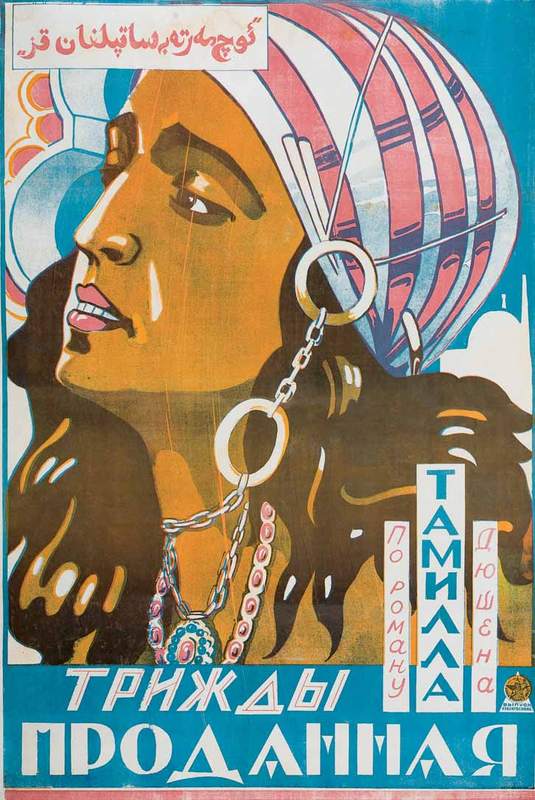

Their titles themselves evidence a negative attitude toward religion per se: “The Purdah,” “The Second Wife,” “In the Shadow of the Mosque” (Uzbekgoskino, 1927), “Thrice Sold” (Tamilla/What She Was Tried For/Women as Commodities, VUFKU [All-Ukraine Photo and Cinema Administration], Odessa, 1927), “The Saint’s Daughter” (1930) and “Ramadan” (Uzbekgoskino, 1933) (201-202). The last one, for example, is about a former feudal bai, kulak and foreign spy try to use the holiday for breaking the fast at the end of the month of Ramadan to disrupt a collective-farm plan for harvesting cotton. The region had quite a few film-making artists, notable among whom was Varsham Nikitich Yeremian (1897-1963), a native of Nagorny Karabakh who worked a good deal in the genre of political and film-advertising posters. He was the production designer later for a whole host of films that played up the topic of the region’s ancient cultural traditions and their most prominent representatives, such as “Nasreddin in Bukhara” (1942), “Takhir and Zukhra” (1945), “The Adventures of Nasreddin” (1947), Alisher Navoi (1948) and “Avicenna” (1957).

Propaganda was developed through the cinema in the Soviet Caucasus to a lesser degree than in Central Asia. Its center in the 1930s was Azerbaidzhan, where the Azgoskinprom association, the Azerbaidzhan State Film-Making Industry, operated. We mentioned earlier one of its documentary films against Shia processions of self-flagellators in Muharram.

In 1934 the silent feature film “Ismet,” or “The Death of Adat,” was produced there (241). The story line of the picture was based on the biography of the first Azerbaidzhani female aviator, Leila Mamedbekova. The film used her example to describe the difficult journey of the emancipation of Muslim women, who rebelled against feudal customs (adats) and managed to secure fulfillment of the right granted them by the Soviet Constitution to be free citizens of their homeland.

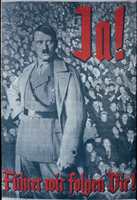

Foreign Parallels

For all its distinctiveness Soviet visual propaganda had obvious parallels with the posters of the USSR’s ideological adversaries from Nazi Germany and the capitalist powers of Europe and the United States. The background of the foreign counterparts of Soviet posters also originates in the political cartoons of World War I. Just as in Russia, the most popular poster artists in the West were formerly cartoonists and artists at wartime newspaper and magazines. But religious themes were of less importance abroad than in the Soviet Union. The reason is that forced state secularization was completed abroad earlier. It was carried out in an especially radical manner in 19th-century France. Other topics were more important for visual propaganda in the second third of the 20th century; some of them, such as the unity of the nation in labor, defined Soviet posters and cartoons between the two wars to the same degree concurrently with Western ones. The indoctrination of the masses in capitalist countries was conducted no less actively than under the socialist and National Socialist regimes.

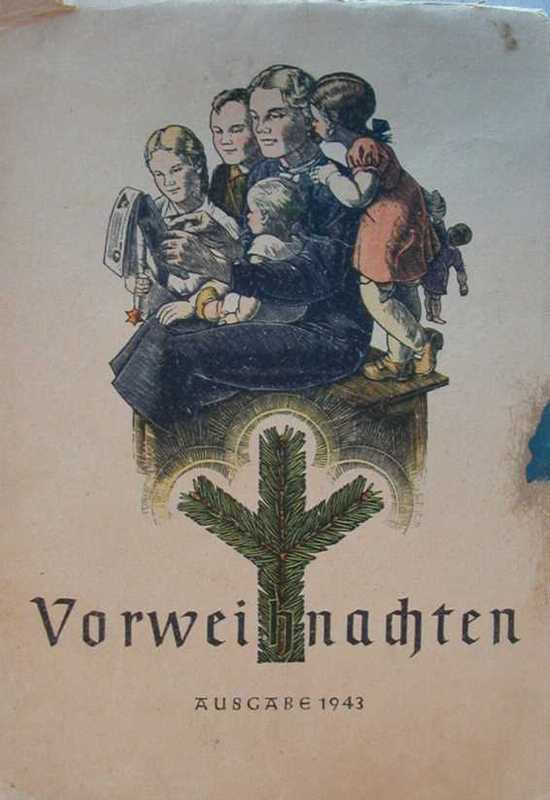

There is more of a similarity between Soviet and Nazi posters. While the target of Soviet cartoonists’ criticism was religion per se, their Nazi counterparts denounced the adherence of Germans to Catholicism, which held a strong position in the centers of National Socialism in the southwestern parts of the country. As in the USSR, Christian symbols were being rooted out in Germany. While preserving the celebration of Christmas, the National Socialists prohibited even the mention of Christ in the context of the holiday, which was dedicated to Him. On Christmas cards the cross replaced a drawing of a Christmas-tree branch (21dop).

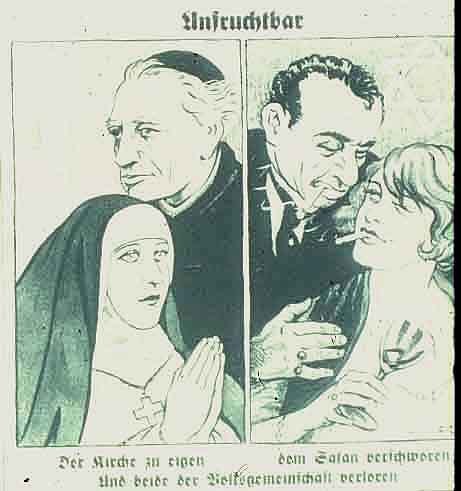

Criticism of Catholicism was tied in with the overall anti-Semitic orientation of the Third Reich’s propaganda. On one of its posters we see two different types of “fallen women.” One of them lives it up in the arms of a Jewish capital with a glass of wine and an expensive cigar at a restaurant, while the other offers prayers under the guidance of a Catholic priest at a monastery. The caption on the drawing refers to the absolute condemnation in National Socialist morality of monasticism, as well as prostitution. “Barren. This one belongs to the Church, that one to Satan. Both are lost to the German race” (22dop). Similar attacks were made in the Soviet Union on the Catholic (in the outlying western regions), Orthodox and Muslim clergy. Posters depicted the clergy of all stripes as exploiters of the common people, encumbering their difficult life with their collections of alms. They also accuse it of preventing the people from fully serving the state. What is also similar in these cartoons are is the orientation toward the moral constancy and masculinity of their (Soviet/Aryan) culture as compared with the inert, feminine, hostile culture.

It was also typical of both Western and Soviet posters between the two world wars to pit “us” against “others.” The image of the “alien” played the role of scapegoat, who was blamed for every conceivable sin. He became responsible for all of the failures and difficulties of modern times. The only difference was in the personification of the “alien.” For Soviet poster artists, it was “the foreign capitalist encirclement” and the enemies of Soviet rule who had found refuge abroad. For the Nazis, it was the worldwide Jewish conspiracy of capitalist and Soviet rulers who were trying to join forces behind the backs of German workers. For the Western powers, it was the Soviet Bolshevik and National Socialist threat, again from abroad. By the beginning of the 1940s the general orientation of Soviet political propaganda had changed. At a time when war was approaching, the authorities decided to put their reliance on the population’s patriotic feelings. The disparagement of prerevolutionary Russia was sharply softened. The Soviet Union began to act like the legal successor of Great Russia in the form of Soviet Russia. The change of policy was immediately reflected in the general appearance of posters, which started to take on great-power, epic hues that resembled the pre-Soviet posters of World War I. Dmitry Moor drew his last works in this genre. The Dagestani artist Khalil-bek Musaiasul, who by that time had made his way to Germany, began working in a similar style, but for National Socialist purposes.

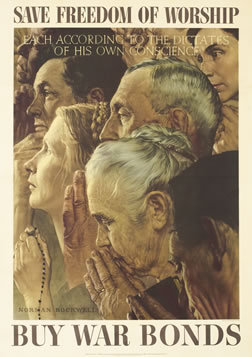

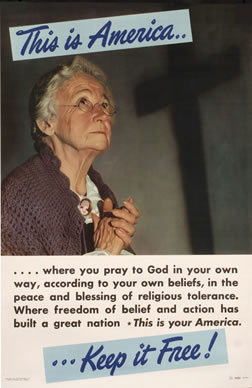

Western posters depicted their states as defenders of the believers in their countries. In the posters of the Western allies in the antifascist coalition, they alone were capable shielding the religious freedom of their citizens from the Soviet and Nazi threat. “Save Freedom of Worship! Buy War Bonds!” appealed a poster issued in 1943 by the popular American artist Norman Rockwell (23dop). “This is America… where you pray to God in your own way, according to your own beliefs, in the peace and blessing of religious tolerance. Where freedom of belief and action has built a great nation. This is your America… Keep it free!,” insists a 1942 photo poster from Sheldon-Claire’s series “Fighting for an Ideal America” (24dop). The rhetoric of these religious posters, of course, was the diametrical opposite of Soviet atheist rhetoric, but in their thrust they often aligned with Soviet posters by playing up the state’s role in the practical exercise of freedom of conscience.

The Soviet East, as a rule, appeared in the posters of the National Socialists and Western powers with an Orientalized look. They portray the Soviet Union as an anachronistic Eastern despotism under Iosif Stalin that posed a threat to the civilized world.

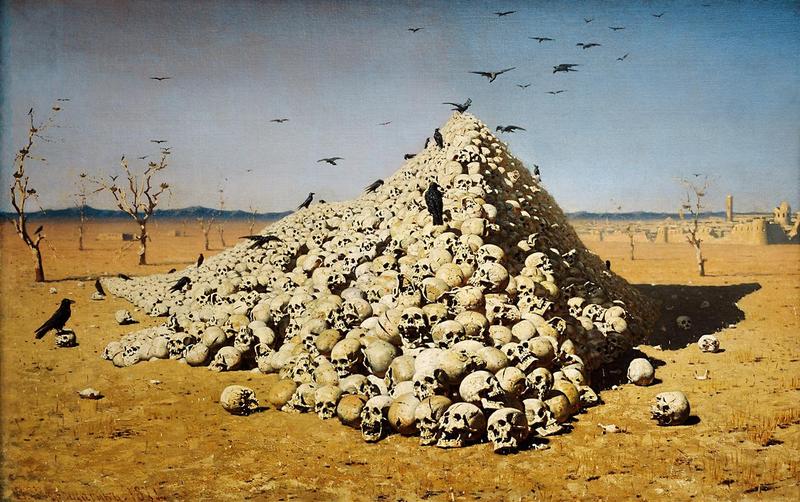

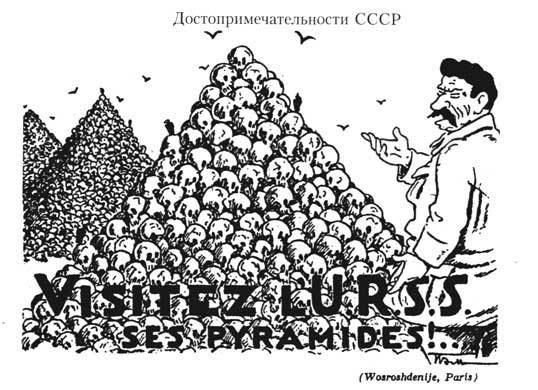

In depicting it, cartoonists used the abundant reservoirs of images of Russian Orientalism, particularly in the works of V. V. Vereshchagin. His “apotheosis of war” with a pile of skulls in the foreground (27dop) became a true business card of Stalin’s regime.

For example, in a French cartoon from the end of the 1930s in the émigré magazine Vozrozhdenie [Renaissance] “Tourist attractions of the USSR: Visit the USSR and its Pyramids!..” (25dop). These and similar rebukes referring to the cannibalistic tendencies of a regime that annihilated millions of its own citizens were, of course, valid, but the images of it in Western cartoons remained extremely far removed from reality. They fit into the overall logic of the Sovietological theory of totalitarianism, in which the totalitarian state is juxtaposed with the society it has enslaved as two hostile external forces. The Muslims and other Eastern peoples of the USSR, who rarely turned up in anti-Soviet cartoons, were portrayed as frozen in their prehistorical everyday life.

The Role of Stalinist Repression